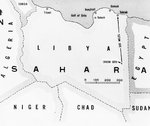

On the afternoon of April 4, 1943, the B-24 bomber 'Lady Be Good' (LBG) took off from Soluch Airstrip in Libya, along with 24 other planes, on a mission to bomb the port at Naples, Italy. The estimated time for the mission was nine hours round trip, and the planes had enough fuel for twelve hours of flight time. Due to strong winds and sandstorms, the planes were forced to take off in small groups. The LBG was one of the last to leave, in a group with two other planes. But these two planes had gotten sand in their engines while taking off and had to turn back, leaving the LBG alone and well behind the other planes.

The crew had to make constant course corrections along the route, due to strong winds, and fell even further behind the other planes. The planes could not communicate with each other by radio, for fear of attracting Nazi fighter planes. By the time the LBG reached the vicinity of the target, the other planes had already dropped their bombs and were on their way back home. Rather than drop its bombs alone, the LBG headed for home and dropped its bombs into the sea along the way. On its way back, the aircraft sent a coded message asking for a directional bearing to Soluch, and was sent one, but after that the plane was not heard from again. An extensive sea search and limited land search were undertaken, but the plane and its crew of nine could not be found. It had been the crew's first combat mission.

The crew members of the 'Lady Be Good' were:

* 1st Lieutenant William J. Hatton, Pilot - Whitestone, New York

* 2d Lieutenant Robert F. Toner, Copilot - North Attelboro, Massachusetts

* 2d Lieutenant Dp Hays, Navigator - Lee's Summit, Missouri

* 2d Lieutenant John S. Woravka, Bombardier - Cleveland, Ohio

* Technical Sergeant Harold J. Ripslinger, Flight Engineer - Saginaw, Michigan

* Technical Sergeant Robert E. LaMotte, Radio Operator - Lake Linden, Michigan

* Staff Sergeant Guy E. Shelley, Gunner/Asst Flight Engineer - New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

* Staff Sergeant Vernon L. Moore, Gunner/Asst Radio Operator - New Boston, Ohio

* Staff Sergeant Samuel R. Adams, Gunner - Eureka, Illinois

The crew had to make constant course corrections along the route, due to strong winds, and fell even further behind the other planes. The planes could not communicate with each other by radio, for fear of attracting Nazi fighter planes. By the time the LBG reached the vicinity of the target, the other planes had already dropped their bombs and were on their way back home. Rather than drop its bombs alone, the LBG headed for home and dropped its bombs into the sea along the way. On its way back, the aircraft sent a coded message asking for a directional bearing to Soluch, and was sent one, but after that the plane was not heard from again. An extensive sea search and limited land search were undertaken, but the plane and its crew of nine could not be found. It had been the crew's first combat mission.

The crew members of the 'Lady Be Good' were:

* 1st Lieutenant William J. Hatton, Pilot - Whitestone, New York

* 2d Lieutenant Robert F. Toner, Copilot - North Attelboro, Massachusetts

* 2d Lieutenant Dp Hays, Navigator - Lee's Summit, Missouri

* 2d Lieutenant John S. Woravka, Bombardier - Cleveland, Ohio

* Technical Sergeant Harold J. Ripslinger, Flight Engineer - Saginaw, Michigan

* Technical Sergeant Robert E. LaMotte, Radio Operator - Lake Linden, Michigan

* Staff Sergeant Guy E. Shelley, Gunner/Asst Flight Engineer - New Cumberland, Pennsylvania

* Staff Sergeant Vernon L. Moore, Gunner/Asst Radio Operator - New Boston, Ohio

* Staff Sergeant Samuel R. Adams, Gunner - Eureka, Illinois