ccheese

Member In Perpetuity

By Matthew Bowers

The Virginian-Pilot

© July 7, 2008

VIRGINIA BEACH

Sgt. Frank Few, swimming away from the ambush, looked back in horror. He saw Japanese swords flashing in the dawn sun over the bodies of his Marine buddies lying on a Guadalcanal beach.

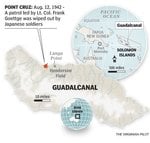

The attack on Aug. 12, 1942, was the end of the ill-fated Goettge Patrol and the beginning of a largely forgotten mystery of World War II.

Three men, including Few, escaped, but rescue parties in the next days found little trace of the rest of the patrol, and no bodies. Sixty-six years later, the 22 men who were lost remain listed as missing in action.

This month, a team of three Radford University researchers and six students, including Trevor Twyford and Sarah Clark of Virginia Beach, will try to find out what happened to them.

The group is headed for the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific armed with ground-penetrating radar. They hope to locate graves within a 6-acre plot on Guadalcanal, find remains or identify artifacts, and return home at month's end with some overdue closure.

"It's not a good subject matter, what we are looking for," said Clark, a senior majoring in psychology and minoring in anthropology. "But if we could actually find them, that would be an amazing thing for the families."

The landing on Guadalcanal in August 1942 marked the end of Japanese advances in the Pacific. It was the first major amphibious assault and offensive by U.S. forces in the war, and the first time they fought the enemy up close.

Things were rough from the beginning, from supply problems to learning to fight in the tropics to realizing how fiercely the Japanese would oppose them.

The Goettge Patrol was one of the harder lessons. Online book excerpts and monographs by Marine historians lay it out: The first week, as Marines struggled for control of the airfield that made Guadalcanal a strategic prize, a Japanese prisoner said others were willing to surrender, many of them hurt and starving.

Lt. Col. Frank Goettge, a Marine football star and the division's top intelligence officer, asked to lead a patrol to find them. He packed a 25-man outfit with more intelligence officers, the division's head surgeon and a top interpreter, along with the prisoner.

Goettge's humanitarian concerns depleted the fighting strength of the patrol and delayed its departure so that the small transport boat ferrying them up the coast landed in pitch dark the night of Aug. 12.

It also landed them in the wrong place - where they were warned not to go because of a heavy concentration of Japanese forces.

Soon after the boat left, the Japanese opened up with machine gun and rifle fire, decimating the patrol. The first shots killed Goettge, according to the accounts.

The apparent butchering of the wounded Marines on the beach became a rallying point for the Americans - and a cautionary tale about expecting any quarter from the Japanese. The fighting on Guadalcanal continued for six months. More than 1,500 Americans and 15,000 Japanese were killed in action. More battles on more islands followed until the war ended in 1945. The Goettge Patrol became a historical footnote.

But not to everyone. Historians believe that the Japanese buried the Americans in trenches, along with some of their own dead, according to Radford University. Various attempts over the past 20 years failed to locate the patrol's remains.

More recently, a private organization said its research indicated a likely site. Greatest Generation MIA Recoveries, which researches those missing in World War II, asked Radford's Forensic Science Institute for help.

Anthropologists Cliff Boyd, co-founder and co-director of the institute; his wife, Donna Boyd, another co-director; and physicist Rhett Herman, also on Radford's faculty, will use archeological techniques to search for the graves. If the radar picks up disturbances in the soil that indicate digging, remains or artifacts, the team will excavate a small area to check. If remains are found, Donna Boyd will determine whether they're American and the approximate date of death.

If members of the patrol are found, the Army Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii will take over the removal.

The Radford search team will have to contend not just with the passage of 66 years, but also with roads and buildings since built in the area.

"If there's something there in the 6 acres and we can get access to it, I think we'll find it," Cliff Boyd said.

Twyford, one of the students from Virginia Beach, said he used some of the same equipment earlier this year to study ice caps in Alaska. "Hopefully all our different specialties will help us find what we're looking for," he said.

Both Twyford and Clark, the other Virginia Beach student, said they knew little about Guadalcanal and the historic battle before getting involved in the Radford project.

"You'd be surprised what you skim over" in history classes, Clark said. She had to look up the Solomon Islands on a map. Traveling to the Pacific battle site was one of her first plane trips.

"If we do find something, I almost see it as part of the job," she said. " But I know it will be emotional if we do find them."

This from today's [Norfolk] Virginian Pilot...

Charles

The Virginian-Pilot

© July 7, 2008

VIRGINIA BEACH

Sgt. Frank Few, swimming away from the ambush, looked back in horror. He saw Japanese swords flashing in the dawn sun over the bodies of his Marine buddies lying on a Guadalcanal beach.

The attack on Aug. 12, 1942, was the end of the ill-fated Goettge Patrol and the beginning of a largely forgotten mystery of World War II.

Three men, including Few, escaped, but rescue parties in the next days found little trace of the rest of the patrol, and no bodies. Sixty-six years later, the 22 men who were lost remain listed as missing in action.

This month, a team of three Radford University researchers and six students, including Trevor Twyford and Sarah Clark of Virginia Beach, will try to find out what happened to them.

The group is headed for the Solomon Islands in the South Pacific armed with ground-penetrating radar. They hope to locate graves within a 6-acre plot on Guadalcanal, find remains or identify artifacts, and return home at month's end with some overdue closure.

"It's not a good subject matter, what we are looking for," said Clark, a senior majoring in psychology and minoring in anthropology. "But if we could actually find them, that would be an amazing thing for the families."

The landing on Guadalcanal in August 1942 marked the end of Japanese advances in the Pacific. It was the first major amphibious assault and offensive by U.S. forces in the war, and the first time they fought the enemy up close.

Things were rough from the beginning, from supply problems to learning to fight in the tropics to realizing how fiercely the Japanese would oppose them.

The Goettge Patrol was one of the harder lessons. Online book excerpts and monographs by Marine historians lay it out: The first week, as Marines struggled for control of the airfield that made Guadalcanal a strategic prize, a Japanese prisoner said others were willing to surrender, many of them hurt and starving.

Lt. Col. Frank Goettge, a Marine football star and the division's top intelligence officer, asked to lead a patrol to find them. He packed a 25-man outfit with more intelligence officers, the division's head surgeon and a top interpreter, along with the prisoner.

Goettge's humanitarian concerns depleted the fighting strength of the patrol and delayed its departure so that the small transport boat ferrying them up the coast landed in pitch dark the night of Aug. 12.

It also landed them in the wrong place - where they were warned not to go because of a heavy concentration of Japanese forces.

Soon after the boat left, the Japanese opened up with machine gun and rifle fire, decimating the patrol. The first shots killed Goettge, according to the accounts.

The apparent butchering of the wounded Marines on the beach became a rallying point for the Americans - and a cautionary tale about expecting any quarter from the Japanese. The fighting on Guadalcanal continued for six months. More than 1,500 Americans and 15,000 Japanese were killed in action. More battles on more islands followed until the war ended in 1945. The Goettge Patrol became a historical footnote.

But not to everyone. Historians believe that the Japanese buried the Americans in trenches, along with some of their own dead, according to Radford University. Various attempts over the past 20 years failed to locate the patrol's remains.

More recently, a private organization said its research indicated a likely site. Greatest Generation MIA Recoveries, which researches those missing in World War II, asked Radford's Forensic Science Institute for help.

Anthropologists Cliff Boyd, co-founder and co-director of the institute; his wife, Donna Boyd, another co-director; and physicist Rhett Herman, also on Radford's faculty, will use archeological techniques to search for the graves. If the radar picks up disturbances in the soil that indicate digging, remains or artifacts, the team will excavate a small area to check. If remains are found, Donna Boyd will determine whether they're American and the approximate date of death.

If members of the patrol are found, the Army Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii will take over the removal.

The Radford search team will have to contend not just with the passage of 66 years, but also with roads and buildings since built in the area.

"If there's something there in the 6 acres and we can get access to it, I think we'll find it," Cliff Boyd said.

Twyford, one of the students from Virginia Beach, said he used some of the same equipment earlier this year to study ice caps in Alaska. "Hopefully all our different specialties will help us find what we're looking for," he said.

Both Twyford and Clark, the other Virginia Beach student, said they knew little about Guadalcanal and the historic battle before getting involved in the Radford project.

"You'd be surprised what you skim over" in history classes, Clark said. She had to look up the Solomon Islands on a map. Traveling to the Pacific battle site was one of her first plane trips.

"If we do find something, I almost see it as part of the job," she said. " But I know it will be emotional if we do find them."

This from today's [Norfolk] Virginian Pilot...

Charles