Shortround6

Lieutenant General

TANSTAAFL

A projectile that needs a small propelling charge may be able to carry that charge inside the projectile.

But if you are looking for high velocity you need a certain amount of propellent to get the projectile (of a certain weight) up to that speed inside the barrel.

Splitting the propellent in two parts, one in the cartridge case and one in the projectile does not make things more efficient. You want 20% more velocity? you need 40% (or more) propellent, how you add that is the question. British 2pdr HV shells lost about 14% of their weight to help get the extra velocity.

Using rockets outside of the barrel solves the problem of higher pressure inside the barrel, doesn't really solve the problem of the needed amount propulsion (energy needed to get X amount of mass up to desired velocity). A small charge in the base of a shell is not going to turn an 88mm/56 into an 88mm/71. That 25% increase (820 to 1000ms) required a 100 increase in propellent and the longer barrel. If you want to use a rocket motor to get rid of the extra barrel length OK, but now you need around 2.5 kg of propellent in the back of the 88mm shell and you need either a longer shell or a much reduce HE charge. Much longer shell may require a different rifling twist in order to stabilize.

Rocket propelled or rocket assisted artillery shells have always had an accuracy problem. Rocket assist was a really big thing in the 1970s/80s with huge gains it range from existing 155mm guns/howitzer and even 105mm howitzers. These worked by delaying the rocket firing for a number of seconds after the projectile left the barrel. The rocket motor fired after the shell had lost some of it's initial velocity and boosted it back up and/or helped maintain velocity. And the rocket fired in thinner air so you need a bit less propellent to fight air resistance. However accuracy was usually poor. The rocket motors did not all fire at the exact same point in the trajectory which is curved so large variations in range. All shells wobble a bit in flight. That is the nose is making a small circle as the shell rotates. When the rocket motor fires the shells tended to take off in a new direction, which in a shell that was still thousands of meters from it's target doesn't have to be a big deviation.

Artillery customers finally gave up and just bought guns with longer barrels and more streamlined projectiles. And that is with 1970s-80s-90s machining capabilities and design and aerodynamics.

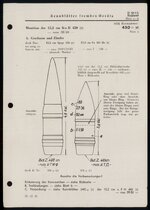

Better shaped projectiles could have done a lot for better performance. German 30mm MK 108 ammo shows some of the difference. The Ausf C was still moving at 370ms at 600meters while the Ausf C shell was doing 370ms at 300 meters when both were fired at 500ms. Ausf C shell arrived at 600 meters about 0.25 seconds sooner. Maybe the Ausf A would have the same time of flight if it was fired at 600ms instead of the 500ms but that would need a lot more propellent and a longer barrel.

Few AA shells were as badly shaped (blunt nose) as the MK 108 Ausf A unless they were WW I left overs.

A projectile that needs a small propelling charge may be able to carry that charge inside the projectile.

But if you are looking for high velocity you need a certain amount of propellent to get the projectile (of a certain weight) up to that speed inside the barrel.

Splitting the propellent in two parts, one in the cartridge case and one in the projectile does not make things more efficient. You want 20% more velocity? you need 40% (or more) propellent, how you add that is the question. British 2pdr HV shells lost about 14% of their weight to help get the extra velocity.

Using rockets outside of the barrel solves the problem of higher pressure inside the barrel, doesn't really solve the problem of the needed amount propulsion (energy needed to get X amount of mass up to desired velocity). A small charge in the base of a shell is not going to turn an 88mm/56 into an 88mm/71. That 25% increase (820 to 1000ms) required a 100 increase in propellent and the longer barrel. If you want to use a rocket motor to get rid of the extra barrel length OK, but now you need around 2.5 kg of propellent in the back of the 88mm shell and you need either a longer shell or a much reduce HE charge. Much longer shell may require a different rifling twist in order to stabilize.

Rocket propelled or rocket assisted artillery shells have always had an accuracy problem. Rocket assist was a really big thing in the 1970s/80s with huge gains it range from existing 155mm guns/howitzer and even 105mm howitzers. These worked by delaying the rocket firing for a number of seconds after the projectile left the barrel. The rocket motor fired after the shell had lost some of it's initial velocity and boosted it back up and/or helped maintain velocity. And the rocket fired in thinner air so you need a bit less propellent to fight air resistance. However accuracy was usually poor. The rocket motors did not all fire at the exact same point in the trajectory which is curved so large variations in range. All shells wobble a bit in flight. That is the nose is making a small circle as the shell rotates. When the rocket motor fires the shells tended to take off in a new direction, which in a shell that was still thousands of meters from it's target doesn't have to be a big deviation.

Artillery customers finally gave up and just bought guns with longer barrels and more streamlined projectiles. And that is with 1970s-80s-90s machining capabilities and design and aerodynamics.

Better shaped projectiles could have done a lot for better performance. German 30mm MK 108 ammo shows some of the difference. The Ausf C was still moving at 370ms at 600meters while the Ausf C shell was doing 370ms at 300 meters when both were fired at 500ms. Ausf C shell arrived at 600 meters about 0.25 seconds sooner. Maybe the Ausf A would have the same time of flight if it was fired at 600ms instead of the 500ms but that would need a lot more propellent and a longer barrel.

Few AA shells were as badly shaped (blunt nose) as the MK 108 Ausf A unless they were WW I left overs.