Yeah, I was going by memory, couldn't remember if it was Army or Navy, just the number 31, so I went with LZ.

I'm shocked, Dave, not your usual degree of care... Are you feeling okay?

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Ad: This forum contains affiliate links to products on Amazon and eBay. More information in Terms and rules

Yeah, I was going by memory, couldn't remember if it was Army or Navy, just the number 31, so I went with LZ.

Actually, no - not having a good life at the moment.I'm shocked, Dave, not your usual degree of care... Are you feeling okay?

Be that as it may, there are pictures of the Stirling kitted out with seats Why else was it so huge when the bomb bay was no longer than a Lancaster and it couldnt actually load very big bombs. It was 17ft longer than a Lancaster with almost the same wingspan, literally a huge waste of space.

from wiki

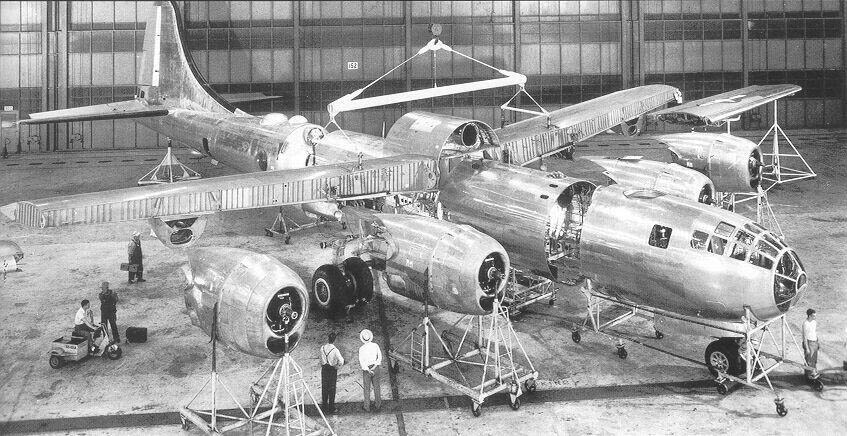

View attachment 693942

As a transport, it made a great glider tug.The Stirling was a good idea crippled be reusing the wrong ideas.

It was a bad bomber, but its draggy high lift wing from the Sunderland made it a half decent transport.

As a transport, it made a great glider tug.

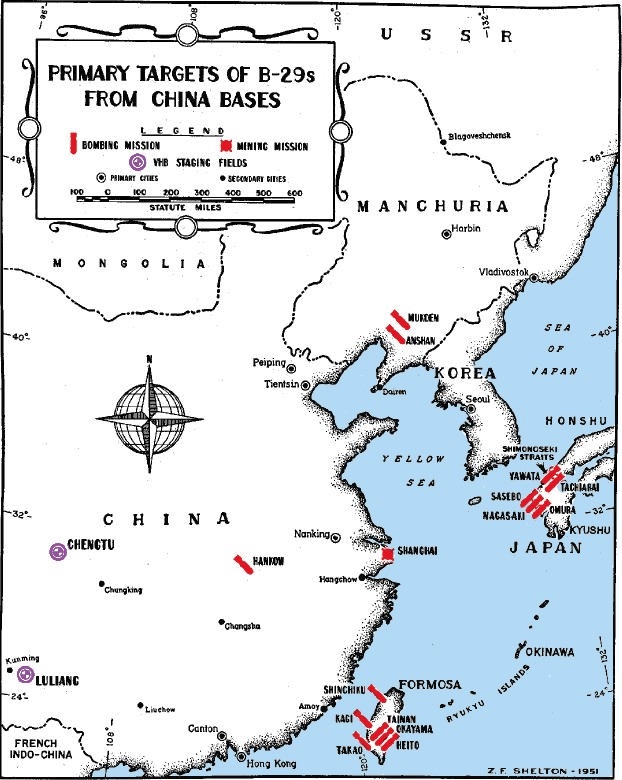

In Tokyo, like all Japanese cities house were built of wood. They burnt very easily. The surviving buildings are built of bricks or concrete. Fire bombing European cities required explosive bombs to destroy the roof and give access to the interior for the incendiaries. The exterior remained standing but the interiors were gutted.View attachment 691693

Without atomic bomb.

Try doing that with B-17s or B-24s.

Or the aerial mining of the costal waters.

The B-29 was not a one trick pony.

View attachment 691693

Without atomic bomb.

Try doing that with B-17s or B-24s.

Or the aerial mining of the costal waters.

Japanese houses were built of wood, they burnt very well in SUMMER. The surviving buildings you can see are built from brick or concrete. European house were built of brick. They required demolition of the roof by explosive bombs, to give access to the interiors for incendiaries.The B-29 was not a one trick pony.

I know - but the the quote I highlighted in bold earlier refers to the specification that the main RAF heavies were built to - Spec P.13/36 "Twin-engined medium bomber for "world-wide use" (Halifax and Manchester/Lancaster built to this - ended up as four engined bombers - absolutely no reference to functionality incorporated into the design for troop transport that I can find - any use as such afterwards was as adaptation)Actually it did. Some of the earlier requirements spelled out the capacity of the bombers when used as a transport.

The 1936 Specification did not, Supermarine may have take advantage of the that, Shorts may have been afraid that the Air Ministry might change their minds and go back to requiring a large troop capacity and so designed it in. Somebody may have correspondence about this.

AS 23 bomber transport

View attachment 694311

predecessor of the Whitley. The Harrow and the Bristol Bombay were built to the same or follow up requirement.

HP Harrows were issued to 5 RAF bomber squadrons, it part because there wasn't anything better and in part because they were better than the HP Heyford which was not built to a dual role specification.

View attachment 694312

Japanese houses were built of wood, they burnt very well in SUMMER.

As I noted previously there were 3 firebombing raids against Japanese cities in Jan/Feb 1945. While the buildings burned just fine, the raids themselves were considered failures because they didn't achieve the mass firestorm effect hoped for.Tokyo was firebombed the first time at the end of winter. The buildings went up fine.

Ambient temperature is only rarely a factor in structural fires -- especially ones started by gasoline-based incendiaries in the first place.

Hang in there bud, we're all in this together, we're always here for you!Actually, no - not having a good life at the moment.

Actually, no - not having a good life at the moment.

Later Chadwick admitted "that it was his inexperience in designing large all-metal aircraft of the rigidity demanded by the specification that had led, in part, to the aircraft coming out overweight" (Kirby again). It is perhaps fortunate therefore that Avro was later able to benefit from that inexperience through the massive weight lifting capacity of the Lancaster as much as the requirements built into the original spec. that couldn't be changed."

The B-29 could perform a number of missions, using a variety of weapons and do it at longer ranges using fewer aircraft than any other bomber if the time.

This photo that has appeared many times has always puzzled me. With two Grand Slams totalling 44,000lb aboard, just how much fuel was it carrying? And therefore what was its potential range? Were they even filled with explosives or sand ballast or effectively just aerodynamic test shapes?

At 22,000lbs, its not as if they can be dropped separately either, is it?This photo that has appeared many times has always puzzled me. With two Grand Slams totalling 44,000lb aboard, just how much fuel was it carrying? And therefore what was its potential range? Were they even filled with explosives or sand ballast or effectively just aerodynamic test shapes?