Good shots Grant!

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A Deep Dive into the Musée de l'Air et de l'Espace

- Thread starter nuuumannn

- Start date

Ad: This forum contains affiliate links to products on Amazon and eBay. More information in Terms and rules

More options

Who Replied?- Thread starter

- #62

Onto the Hall de l'Entre-Deux-Guerres, or Between-the-Wars Hall and some intriguing civilian operated aeroplanes, beginning with this Dewoitine D.530 fighter demonstration aircraft. The D.530 was the last of Emile Dewoitine's lightweight parasol fighters, exemplified by the excellent little D.27, which was designed to meet a 1926 specification for a lightweight fighter and remained in Swiss military service with the Fliegertruppe until 1940. Following structural issues with the D.27's wing design, Dewoitine reworked the aircraft to produce the newly designated D.53, of which only seven were completed, including a single example designated D.532 fitted with a supercharged Rolls-Royce Kestrel. This aircraft demonstrated excellent performance for its time, but oscillation in the empennage resulted in the Kestrel being replaced with a 500 hp Hispano-Suiza HS.12Mb and a redesignation as the D.534. Two D.531s powered by HS.12Mb engines served in the Spanish Civil War on the Republican side, where they were known as Dewoitinillos or Dewoitine pequenos, or Little Dewoitines since the bigger D.371 fighter was in use in theatre. Note that the French system of designation saw the original design furnished with a numerical designator, such as D.53, with subsequent variants with significant differences, such as different engines or armament from the base model receiving sequential numerical suffixes after the initial designator. The D.530 from the side as you enter the building.

Musee de l'Air 131

Musee de l'Air 131

Powered by a 500 hp Hispano-Suiza HS.12Mb, the only example of the pugnacious D.530 never saw military service with the Armée de l'Air and was released from the Argenteuil factory for use by famed aerobatic pilot Marcel Doret as a demonstration aircraft at international aerobatic meets. Born in 1896, Doret enlisted with the army during the Great War, but after injury transferred to aviation at the tender age of 18, where his piloting skills were noted, becoming a test pilot post-war, firstly with Renault, then after being noticed by Emile Dewoitine, with his firm at Toulouse, rising to the status of Chief Test Pilot with Dewoitine. During his career, he partook in a number of long-distance flights, one of which was an attempt at a flight from Paris to Tokyo in 1931, but the aircraft crashed due to icing over the Urals and Doret was the only survivor of his three-man crew. As an aerobatic pilot, he earned fame in France, coming third at a meet at Dübendorf, Switzerland in 1927, against famous German pilot Gerhard Fieseler. Following this meet, the two pilots devised an aerobatic competition to be held at Berlin's Tempelhof aerodrome later that year, which over 100,000 spectators witnessed, where each pilot was to fly each other's aeroplanes. Doret was crowned "King Of The Air", but the honour was short-lived as Fieseler was crowned aerobatic World Champion in 1934 in Paris. This is, of course, the very same Gerhard Fieseler of the aircraft company responsible for the little-known and not very prevalent (sarcasm) Fi-156 Storch observation aircraft, which was built in France post-war as the Morane-Saulnier Criquet. Doret's last mount as an aerobatic pilot displaying its brutish nasal features.

Musee de l'Air 134

Musee de l'Air 134

Remaining loyal to Dewoitine during the war, Doret commanded 1 Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur (FFI) Groupe de Chasse, composite squadron operating the D.520 fighter and thus saw combat in two world wars as an aviator, but post-war, Doret continued to fly the D.530 during public aerobatic demonstrations until his death in 1955 of cancer, his last flight shortly before his passing. Decorated with the sunburst red stripes on its upper wing and hori-stab surfaces as a reminder of the D.27 that he flew at many of his Between-the-Wars displays, the Dewoitine survives in honour of Doret's skill as an airman and holds a special place in the museum's collection.

Musee de l'Air 136

Musee de l'Air 136

An example of the extensively used Hispano-Suiza 12Y Moteur Cannon engine, this one a 12Y-45 variant that powered the famous, or rather infamous D.520 fighter, which wiki.fr tells us about: "A real effort to improve the performance of the engine in 1938 resulted in the Hispano-Suiza 12Y-45, which used the S-39-H3 supercharger co-designed by André Planiol and Polish engineer Joseph Szydlowski. The Szydlowski-Planiol device was larger, but much more efficient than the indifferent Hispano-Suiza models. When used with 100 octane fuel, the supercharger boosted to the -21's 7:1, increasing power to 900 hp (670 kW). Combined with the Ratier constant-speed propeller, this allowed the D.520 to perform as well as contemporary designs from Germany and England."

Musee de l'Air 137

Musee de l'Air 137

An example of the less successful Hisso 18R engine, the 18Sbr originally developed for the Schneider Trophy races, information of which from wiki.fr:

"After failing to enter the Schneider Trophy seaplane race for several years, the French Ministère de l'Air decided to enter the 1929 competition. Two companies were tasked with designing and building floatplane racers to compete with the entries from Italy and Great Britain, resulting in the Nieuport-Delage NiD-450 and Bernard H.V.120, both of which were powered by the specially designed Hispano-Suiza 18R engines.

To power the racers Hispano-Suiza married three six-cylinder blocks from the Hispano-Suiza 12Nb to a common crankshaft/crankcase, set at 80° to each other. Retaining the 150 mm (5.91 in) bore and 170 mm (6.69 in) stroke of the 12Nb, the 18R had the compression ratio increased from 6.25:1 to 10:1 with a total displacement of 54.075L (3,299.8ci). Each cylinder aspirated through two valves operated by single overhead cam-shafts with ignition from two spark plugs set on opposite sides of the combustion chamber supplied by magnetos at the rear of the engine. Fuel metering was carried out by nine carburetors each supplying two cylinders.

Construction of the 18R was largely of Elektron magnesium alloy for body components with high strength steels for highly loaded parts such as the crankshaft. In common with many multiple bank and radial engines the pistons were connected to the crankshaft via master and slave connecting rods; the central vertical bank was served by the master rod which housed the big-end bearing with connecting rods articulating from this to the other two banks. The 18R was available with or without a Farman (bevel planetary) reduction gear.

Development issues delayed production of the engine, with the first geared drive engine delivered to Nieuport-Delage in October 1929, a month after the 1929 Schneider Trophy race. Despite the effort put into its development the 18R proved to be unreliable and unable to achieve the expected power output. The poor performance of the 18R prompted the development of the 18S, a de-rated version intended for commercial use. Reducing the compression ratio to 6.2:1 at a maximum rpm of 2,000 and replacing the Elektron with aluminium alloy, the 18S was available with or without the Farman reduction gear, but was not a success, only powering the Ford 14A in the pylon mounted central nacelle."

The engine's career was not a success, only powering four individual aeroplanes, all Schneider Trophy racers, but it could not compete against its contemporaries produced by Rolls-Royce.

Musee de l'Air 138

Musee de l'Air 138

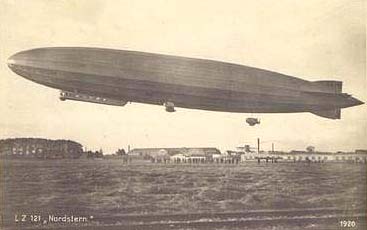

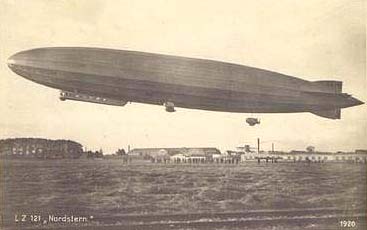

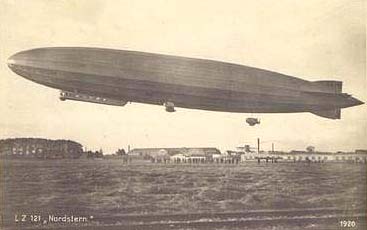

An example of the Daimler Benz DB602 V-16 diesel engine, of which five powered the giant airship LZ 129 Hindenburg. Some information: "Each of Hindenburg's four LOF-6 (DB-602) 16-cylinder engines had an output of 1320 hp @ 1650 RPM (maximum power), and 900 hp @ 1480 RPM. The normal cruise setting was 1350 RPM, generating approximately 850 hp, and this setting was usually not adjusted during an ocean crossing. The engines were started with compressed air, and could be started, stopped, and reversed in flight. Using 2:1 reduction gearing, each engine drove a 4-bladed, fixed-pitch, 19.7′ diameter metal-sheathed wooden propeller (created from two 2-bladed props fused together)."

From here, a bumper page packed with juicy detail about the Hindenburg: Hindenburg Design and Technology | Airships.net

The DB 602, or LOF.6 was originally designed in the early 1930s and rivalled the engine type of the British Airship R.101, the Beardmore Tornado in power output, but was significantly lighter, reflecting both Benz's knowledge of metallurgy in engine construction and Beardmore's decision to develop the Tornado from a locomotive engine. Modified for marine applications, the engine saw use in a triple installation in four of the notorious Schnellboote fast torpedo boats, in S 10 through 13.

Musee de l'Air 139

Musee de l'Air 139

joining the Junkers Jumo 211 previously mentioned at the museum is this Jumo 205, an example of the first and for many years the only aviation types of diesel in regular operation. Info for the technophiles from wiki:

"These engines all used a two-stroke cycle with 12 pistons sharing six cylinders, piston crown to piston crown in an opposed configuration. This unusual configuration required two crankshafts, one at the bottom of the cylinder block and the other at the top, geared together. The pistons moved towards each other during the operating cycle. Intake and exhaust manifolds were duplicated on both sides of the block. Two cam-operated injection pumps per cylinder were used, each feeding two nozzles, for four nozzles per cylinder in all.

As is typical of two-stroke designs, the Jumos used no valves, but rather fixed intake and exhaust port apertures cut into the cylinder liners during their manufacture, which were uncovered when the pistons reached a certain point in their strokes. Normally, such designs have poor volumetric efficiency because both ports open and close at the same time and are generally located across from each other in the cylinder. This leads to poor scavenging of the burnt charge, which is why valveless two-strokes generally produce smoke and are inefficient.

The Jumo solved this problem to a very large degree through clever arrangement of the ports. The intake port was located under the "lower" piston, while the exhaust port was under the "upper". The lower crankshaft ran 11° behind the upper, meaning that the exhaust ports opened, and even more importantly, closed first, allowing proper scavenging. This system made the two-stroke Jumos run as cleanly and almost as efficiently as four-stroke engines using valves, but with considerably less complexity.

Some downside exists to this system, as well. For one, since matching pistons were not closing at quite the same time, but one ran "ahead" of the other, the engine could not run as smoothly as a true opposed-style engine. In addition, the power from the two opposing crankshafts had to be geared together, adding weight and complexity, a problem the design shared with H-block engines.

In the Jumo, these problems were avoided to some degree by taking power primarily from the "upper" shaft, somewhat offset upwards on the engine's front end. All of the accessories, such as fuel pumps, injectors and the scavenging compressor, were run from the lower shaft, meaning over half of its power was already used up. What was left over was then geared to the upper shaft, which ran the engine's propeller. In all, about three-quarters of the power to the engine's propeller came from the upper crankshaft. In theory, the flat layout of the engine could have allowed it to be installed inside the thick wings of larger aircraft, such as airliners and bombers. Details of the oil scavenging system suggest this was not possible and the engine had to be run "vertically", as it was on all designs using it.

Because the temperature of the exhaust gases of the Jumo diesel engines was substantially lower than that of comparable carburettor engines, it was easier to add a turbocharger for higher altitudes. This was explored in the Jumo 207 which used the energy of the exhaust gases to increase the power at high altitudes."

The engine saw use in World War Two in nautically inclined aircraft as the Blohm und Voss Bv 138 trimotor flying boat and the massive Bv 222 Wiking six engined flying boat, Dornier Do 18 and 26 flying boats, and the land-based Ju 86 bomber. Note the triangular Junkers badges on the front and below the upper casing.

Musee de l'Air 140

Musee de l'Air 140

Lastly for today, another Junkers product, the ground-breaking F 13 passenger aircraft, the world's first all-metal airliner. Seeing service on almost every continent, the F 13 had a lengthy and distinguished career, first flying on 25 June 1919, signifying a technological leap forward and the eventual resurgence of Germany as an aeronautical power in the Between-the-Wars years, despite the country being racked by treaty restrictions. The museum's F 13 was one of seven seized by France as war reparations, this one being Nr 609.

Musee de l'Air 141

Musee de l'Air 141

Junkers' corrugated aircraft features similar construction techniques, not being built like other aircraft types out of longitudinals, frames, and stringers covered in a semi-monocoque stressed skin outer covering. Instead, Junkers built the aircraft's skin as complete sections without separate internal bracing; the fuselage featuring bulkheads that provided shape that was covered in sections of outer skin with partial framework attached to the skin interior and the external corrugation layer providing rigidity. The wings were the same in that they did not feature internal ribs as conventional wing structures did, the supporting structure is built into the wing outer skin that fits over a multi-spar structure, with frames for rigidity at juncture locations, such as where the wings attach to the fuselage but not uniformly throughout. The Ju 87, a smooth-skinned Junkers type also featured this method of construction. Typical of the Junkers externally corrugated method, the F.13 resembles a backyard shed in appearance, a front-on view doing little to dispel the notion.

Musee de l'Air 142

Musee de l'Air 142

Wiki tells us some pertinent information: "The F 13 was a very advanced aircraft when built, an aerodynamically clean all-metal low-wing cantilever (without external bracing) monoplane. Even later in the 1920s, it and other Junkers types were unusual as unbraced monoplanes in a biplane age, with only Fokker's designs of comparable modernity. It was the world's first all-metal passenger aircraft and Junkers' first commercial aircraft.

The designation letter F stood for Flugzeug, aircraft; it was the first Junkers aeroplane to use this system. Earlier Junkers notation labelled it J 13. Russian-built aircraft used the designation Ju 13.

Like all Junkers' duralumin-structured designs, from the 1918 J 7 to the 1932 Ju 46, (some 35 models), it used an aluminium alloy (duralumin) structure entirely covered with Junkers' characteristic corrugated and stressed duralumin skin. Internally, the wing was built upon nine circular cross-section duralumin spars with transverse bracing. All control surfaces were horn-balanced.

Behind the single-engine was a semi-enclosed cockpit for the crew, roofed but without side glazing. There was an enclosed and heated cabin for four passengers with windows and doors in the fuselage sides. Passenger seats were fitted with seat belts, unusual for the time. The F 13 used a fixed conventional split landing gear with a rear skid, though some variants landed on floats or on skis.

The F 13 first flew on 25 June 1919, powered by a 127 kW (170 hp) Mercedes D IIIa inline upright water-cooled engine. The first production machines had a wing of greater span and area and had the more powerful 140 kW (185 hp) BMW IIIa upright inline water-cooled motor.

Many variants were built using Mercedes, BMW, Junkers, and Armstrong Siddeley Puma liquid-cooled inline engines, and Gnome-Rhône Jupiter and Pratt & Whitney Hornet air-cooled radial engines. The variants were mostly distinguished by a two-letter code, the first letter signifying the airframe and the second the engine. Junkers L5-engined variants all had the second letter -e, so type -fe was the long fuselage -f airframe with an L5 engine."

A view from above highlights both the unique Junkers construction and its modern look for a 1920s vintage aeroplane.

Musee de l'Air 157

Musee de l'Air 157

That's all for today, more to come from the Between-The-Wars Hall.

Powered by a 500 hp Hispano-Suiza HS.12Mb, the only example of the pugnacious D.530 never saw military service with the Armée de l'Air and was released from the Argenteuil factory for use by famed aerobatic pilot Marcel Doret as a demonstration aircraft at international aerobatic meets. Born in 1896, Doret enlisted with the army during the Great War, but after injury transferred to aviation at the tender age of 18, where his piloting skills were noted, becoming a test pilot post-war, firstly with Renault, then after being noticed by Emile Dewoitine, with his firm at Toulouse, rising to the status of Chief Test Pilot with Dewoitine. During his career, he partook in a number of long-distance flights, one of which was an attempt at a flight from Paris to Tokyo in 1931, but the aircraft crashed due to icing over the Urals and Doret was the only survivor of his three-man crew. As an aerobatic pilot, he earned fame in France, coming third at a meet at Dübendorf, Switzerland in 1927, against famous German pilot Gerhard Fieseler. Following this meet, the two pilots devised an aerobatic competition to be held at Berlin's Tempelhof aerodrome later that year, which over 100,000 spectators witnessed, where each pilot was to fly each other's aeroplanes. Doret was crowned "King Of The Air", but the honour was short-lived as Fieseler was crowned aerobatic World Champion in 1934 in Paris. This is, of course, the very same Gerhard Fieseler of the aircraft company responsible for the little-known and not very prevalent (sarcasm) Fi-156 Storch observation aircraft, which was built in France post-war as the Morane-Saulnier Criquet. Doret's last mount as an aerobatic pilot displaying its brutish nasal features.

Remaining loyal to Dewoitine during the war, Doret commanded 1 Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur (FFI) Groupe de Chasse, composite squadron operating the D.520 fighter and thus saw combat in two world wars as an aviator, but post-war, Doret continued to fly the D.530 during public aerobatic demonstrations until his death in 1955 of cancer, his last flight shortly before his passing. Decorated with the sunburst red stripes on its upper wing and hori-stab surfaces as a reminder of the D.27 that he flew at many of his Between-the-Wars displays, the Dewoitine survives in honour of Doret's skill as an airman and holds a special place in the museum's collection.

An example of the extensively used Hispano-Suiza 12Y Moteur Cannon engine, this one a 12Y-45 variant that powered the famous, or rather infamous D.520 fighter, which wiki.fr tells us about: "A real effort to improve the performance of the engine in 1938 resulted in the Hispano-Suiza 12Y-45, which used the S-39-H3 supercharger co-designed by André Planiol and Polish engineer Joseph Szydlowski. The Szydlowski-Planiol device was larger, but much more efficient than the indifferent Hispano-Suiza models. When used with 100 octane fuel, the supercharger boosted to the -21's 7:1, increasing power to 900 hp (670 kW). Combined with the Ratier constant-speed propeller, this allowed the D.520 to perform as well as contemporary designs from Germany and England."

An example of the less successful Hisso 18R engine, the 18Sbr originally developed for the Schneider Trophy races, information of which from wiki.fr:

"After failing to enter the Schneider Trophy seaplane race for several years, the French Ministère de l'Air decided to enter the 1929 competition. Two companies were tasked with designing and building floatplane racers to compete with the entries from Italy and Great Britain, resulting in the Nieuport-Delage NiD-450 and Bernard H.V.120, both of which were powered by the specially designed Hispano-Suiza 18R engines.

To power the racers Hispano-Suiza married three six-cylinder blocks from the Hispano-Suiza 12Nb to a common crankshaft/crankcase, set at 80° to each other. Retaining the 150 mm (5.91 in) bore and 170 mm (6.69 in) stroke of the 12Nb, the 18R had the compression ratio increased from 6.25:1 to 10:1 with a total displacement of 54.075L (3,299.8ci). Each cylinder aspirated through two valves operated by single overhead cam-shafts with ignition from two spark plugs set on opposite sides of the combustion chamber supplied by magnetos at the rear of the engine. Fuel metering was carried out by nine carburetors each supplying two cylinders.

Construction of the 18R was largely of Elektron magnesium alloy for body components with high strength steels for highly loaded parts such as the crankshaft. In common with many multiple bank and radial engines the pistons were connected to the crankshaft via master and slave connecting rods; the central vertical bank was served by the master rod which housed the big-end bearing with connecting rods articulating from this to the other two banks. The 18R was available with or without a Farman (bevel planetary) reduction gear.

Development issues delayed production of the engine, with the first geared drive engine delivered to Nieuport-Delage in October 1929, a month after the 1929 Schneider Trophy race. Despite the effort put into its development the 18R proved to be unreliable and unable to achieve the expected power output. The poor performance of the 18R prompted the development of the 18S, a de-rated version intended for commercial use. Reducing the compression ratio to 6.2:1 at a maximum rpm of 2,000 and replacing the Elektron with aluminium alloy, the 18S was available with or without the Farman reduction gear, but was not a success, only powering the Ford 14A in the pylon mounted central nacelle."

The engine's career was not a success, only powering four individual aeroplanes, all Schneider Trophy racers, but it could not compete against its contemporaries produced by Rolls-Royce.

An example of the Daimler Benz DB602 V-16 diesel engine, of which five powered the giant airship LZ 129 Hindenburg. Some information: "Each of Hindenburg's four LOF-6 (DB-602) 16-cylinder engines had an output of 1320 hp @ 1650 RPM (maximum power), and 900 hp @ 1480 RPM. The normal cruise setting was 1350 RPM, generating approximately 850 hp, and this setting was usually not adjusted during an ocean crossing. The engines were started with compressed air, and could be started, stopped, and reversed in flight. Using 2:1 reduction gearing, each engine drove a 4-bladed, fixed-pitch, 19.7′ diameter metal-sheathed wooden propeller (created from two 2-bladed props fused together)."

From here, a bumper page packed with juicy detail about the Hindenburg: Hindenburg Design and Technology | Airships.net

The DB 602, or LOF.6 was originally designed in the early 1930s and rivalled the engine type of the British Airship R.101, the Beardmore Tornado in power output, but was significantly lighter, reflecting both Benz's knowledge of metallurgy in engine construction and Beardmore's decision to develop the Tornado from a locomotive engine. Modified for marine applications, the engine saw use in a triple installation in four of the notorious Schnellboote fast torpedo boats, in S 10 through 13.

joining the Junkers Jumo 211 previously mentioned at the museum is this Jumo 205, an example of the first and for many years the only aviation types of diesel in regular operation. Info for the technophiles from wiki:

"These engines all used a two-stroke cycle with 12 pistons sharing six cylinders, piston crown to piston crown in an opposed configuration. This unusual configuration required two crankshafts, one at the bottom of the cylinder block and the other at the top, geared together. The pistons moved towards each other during the operating cycle. Intake and exhaust manifolds were duplicated on both sides of the block. Two cam-operated injection pumps per cylinder were used, each feeding two nozzles, for four nozzles per cylinder in all.

As is typical of two-stroke designs, the Jumos used no valves, but rather fixed intake and exhaust port apertures cut into the cylinder liners during their manufacture, which were uncovered when the pistons reached a certain point in their strokes. Normally, such designs have poor volumetric efficiency because both ports open and close at the same time and are generally located across from each other in the cylinder. This leads to poor scavenging of the burnt charge, which is why valveless two-strokes generally produce smoke and are inefficient.

The Jumo solved this problem to a very large degree through clever arrangement of the ports. The intake port was located under the "lower" piston, while the exhaust port was under the "upper". The lower crankshaft ran 11° behind the upper, meaning that the exhaust ports opened, and even more importantly, closed first, allowing proper scavenging. This system made the two-stroke Jumos run as cleanly and almost as efficiently as four-stroke engines using valves, but with considerably less complexity.

Some downside exists to this system, as well. For one, since matching pistons were not closing at quite the same time, but one ran "ahead" of the other, the engine could not run as smoothly as a true opposed-style engine. In addition, the power from the two opposing crankshafts had to be geared together, adding weight and complexity, a problem the design shared with H-block engines.

In the Jumo, these problems were avoided to some degree by taking power primarily from the "upper" shaft, somewhat offset upwards on the engine's front end. All of the accessories, such as fuel pumps, injectors and the scavenging compressor, were run from the lower shaft, meaning over half of its power was already used up. What was left over was then geared to the upper shaft, which ran the engine's propeller. In all, about three-quarters of the power to the engine's propeller came from the upper crankshaft. In theory, the flat layout of the engine could have allowed it to be installed inside the thick wings of larger aircraft, such as airliners and bombers. Details of the oil scavenging system suggest this was not possible and the engine had to be run "vertically", as it was on all designs using it.

Because the temperature of the exhaust gases of the Jumo diesel engines was substantially lower than that of comparable carburettor engines, it was easier to add a turbocharger for higher altitudes. This was explored in the Jumo 207 which used the energy of the exhaust gases to increase the power at high altitudes."

The engine saw use in World War Two in nautically inclined aircraft as the Blohm und Voss Bv 138 trimotor flying boat and the massive Bv 222 Wiking six engined flying boat, Dornier Do 18 and 26 flying boats, and the land-based Ju 86 bomber. Note the triangular Junkers badges on the front and below the upper casing.

Lastly for today, another Junkers product, the ground-breaking F 13 passenger aircraft, the world's first all-metal airliner. Seeing service on almost every continent, the F 13 had a lengthy and distinguished career, first flying on 25 June 1919, signifying a technological leap forward and the eventual resurgence of Germany as an aeronautical power in the Between-the-Wars years, despite the country being racked by treaty restrictions. The museum's F 13 was one of seven seized by France as war reparations, this one being Nr 609.

Junkers' corrugated aircraft features similar construction techniques, not being built like other aircraft types out of longitudinals, frames, and stringers covered in a semi-monocoque stressed skin outer covering. Instead, Junkers built the aircraft's skin as complete sections without separate internal bracing; the fuselage featuring bulkheads that provided shape that was covered in sections of outer skin with partial framework attached to the skin interior and the external corrugation layer providing rigidity. The wings were the same in that they did not feature internal ribs as conventional wing structures did, the supporting structure is built into the wing outer skin that fits over a multi-spar structure, with frames for rigidity at juncture locations, such as where the wings attach to the fuselage but not uniformly throughout. The Ju 87, a smooth-skinned Junkers type also featured this method of construction. Typical of the Junkers externally corrugated method, the F.13 resembles a backyard shed in appearance, a front-on view doing little to dispel the notion.

Wiki tells us some pertinent information: "The F 13 was a very advanced aircraft when built, an aerodynamically clean all-metal low-wing cantilever (without external bracing) monoplane. Even later in the 1920s, it and other Junkers types were unusual as unbraced monoplanes in a biplane age, with only Fokker's designs of comparable modernity. It was the world's first all-metal passenger aircraft and Junkers' first commercial aircraft.

The designation letter F stood for Flugzeug, aircraft; it was the first Junkers aeroplane to use this system. Earlier Junkers notation labelled it J 13. Russian-built aircraft used the designation Ju 13.

Like all Junkers' duralumin-structured designs, from the 1918 J 7 to the 1932 Ju 46, (some 35 models), it used an aluminium alloy (duralumin) structure entirely covered with Junkers' characteristic corrugated and stressed duralumin skin. Internally, the wing was built upon nine circular cross-section duralumin spars with transverse bracing. All control surfaces were horn-balanced.

Behind the single-engine was a semi-enclosed cockpit for the crew, roofed but without side glazing. There was an enclosed and heated cabin for four passengers with windows and doors in the fuselage sides. Passenger seats were fitted with seat belts, unusual for the time. The F 13 used a fixed conventional split landing gear with a rear skid, though some variants landed on floats or on skis.

The F 13 first flew on 25 June 1919, powered by a 127 kW (170 hp) Mercedes D IIIa inline upright water-cooled engine. The first production machines had a wing of greater span and area and had the more powerful 140 kW (185 hp) BMW IIIa upright inline water-cooled motor.

Many variants were built using Mercedes, BMW, Junkers, and Armstrong Siddeley Puma liquid-cooled inline engines, and Gnome-Rhône Jupiter and Pratt & Whitney Hornet air-cooled radial engines. The variants were mostly distinguished by a two-letter code, the first letter signifying the airframe and the second the engine. Junkers L5-engined variants all had the second letter -e, so type -fe was the long fuselage -f airframe with an L5 engine."

A view from above highlights both the unique Junkers construction and its modern look for a 1920s vintage aeroplane.

That's all for today, more to come from the Between-The-Wars Hall.

Last edited:

Snautzer01

Marshal

- 46,292

- Mar 26, 2007

Again a nice read. Thank you

Crimea_River

Marshal

Excellent as always Grant. Thanks for the effort you put into these interesting posts.

Nice shots Grant!

- Thread starter

- #67

Thanks again guys, yes, Andy, that's why they come and go - it takes time to collate and sift through translations, but helps me with research too, because this French stuff is just not in our purview, so it's a learning experience.

So, we continue with this fuselage section of a Farman F.60 Goliath airliner, a pioneering type that saw service throughout the 20s but began life as a bomber in 1918. Here's some information about it from the usual source:

"The Goliath was initially designed in 1918 as a heavy bomber capable of carrying 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) of bombs with a range of 1,500 km (930 mi). It was a fixed-undercarriage three-bay biplane of fabric-covered wood construction, powered by two Salmson 9Z engines. It had a simple and robust, yet light structure. The wings were rectangular with a constant profile with aerodynamically balanced ailerons fitted to both upper and lower wings.

It was undergoing initial testing when World War I came to an end and Farman realized there would be no orders for his design. Nonetheless he was quick to understand that the big, box-like fuselage of the Goliath could be easily modified to convert the aircraft into an airliner. Commercial aviation was beginning to be developed and was in need of purpose-built aircraft. With the new passenger cabin arrangement, the Goliath could carry up to 12 or 14 passengers. It had large windows to give the passengers a view of the surroundings. The Salmson engines could be replaced by other types (Renault, Lorraine) if a customer desired it. Approximately 60 F.60 Goliaths were built. Between 1927 and 1929, eight Goliaths with various engines were built under licence in Czechoslovakia, four by Avia and four by Letov."

The history of the Goliath is fascinating and although only 60 were built the type was operated by lots of different airlines around the world, but it suffered a high accident rate. This particular example, F-HMFU, was employed by Air Union as Île de France between Paris and London (Croydon), but in October 1925 it suffered a crash in East Sussex, resulting in the deaths of three passengers and the injuring of two more. It remained registered until 1932 and the fuselage was recovered, but the aircraft never flew again. It is the only surviving section of a Goliath airliner.

Musee de l'Air 143

Musee de l'Air 143

This next aircraft is one of the three most important aircraft in the museum's collection, according to the website. It is of course the striking red Breguet XIX TF Super Bidon Point d'Interrogation, or simply "?". Following from Charles Lindberg's historic solo Atlantic Crossing in 1927, On 1 September 1930, Captain Dieudonne Costes and Navigator Maurice Bellonte took off from Le Bourget, beginning their transatlantic crossing, arriving in the United States at Curtiss Field, New York on the 3rd, after a 37-hour 12-minute flight that covered 3850 miles. Lindberg was there to meet the two Frenchmen. A significant feat, as owing to the prevailing winds, an east-to-west aerial crossing is eminently more difficult; the first being by the rigid airship R.34, a mere two weeks after John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown's Atlantic crossing in a Vickers Vimy in June 1919. The Super Bidon wasn't the first aeroplane to make the crossing in a westerly direction, in 1928 the Junkers W 33L D 1167 Bremen, piloted by Hermann Koehl, with Baron Gunther von Huenefeld and Commandant James Fitzmaurice aboard became the first, flying between Baldonnel, near Dublin and New Foundland. The Super Bidon in its cherry red colour scheme, sitting on top of a display about transatlantic crossings by air.

Musee de l'Air 147

Musee de l'Air 147

First flying on 23 July 1928, the Point d'Interrogation was the last of three TR, or Transatlantique variants built, but it was converted into a TF Super Bidon, which involved numerous modifications, including extending the wingspan, lengthening the fuselage and installing increased fuel tankage. Undertaking sponsorship from Hispano-Suiza, the aircraft's engine manufacturer, the aircraft's manufacturer Breguet and an anonymous benefactor, Costes and Bellonte began preparations for an Atlantic crossing from Paris in 1929. Adorning the aircraft was a white question mark, a nod to the anonymous benefactor, which it became known for, as well as the stork insignia of the Escadrille des Cigognes of Great War fame, which conveniently served as the emblem of Hispano-Suiza. Taking off on 13 July, bad weather hampered the flight on the southern route via the Azores and after covering 1600 miles, Costes elected to return to Paris, not wishing to risk the deteriorating conditions. To maintain the support of their sponsors the duo flew a number of record-breaking flights following their first aborted Atlantic crossing, which included a flight from Paris to Moullart in Manchuria, a journey of 4319 miles in September 1929. A number of circular endurance flights were also flown before the pair and their bright red biplane set off across the Atlantic for a second time. These are recorded on the aircraft's flanks. The mysterious benefactor from whence came its name? The perfume maker Coty!

Musee de l'Air 146

Musee de l'Air 146

Their next attempt was to be made only if the weather was favourable and an agent from the French meteorological office kept a close eye on the weather prior to the flight, enabling a successful crossing in September 1930. Powered by a 650 hp Hispano-Suiza 12Nb engine, the aircrew sat in open cockpits with shielding but were entirely exposed during the flight. Costes' instrumentation was typical of the period, being very crude, with a minimum of dials, dominated by a big compass directly in front of him. After landing in New York, Costes and Bellonte received a ticker-tape parade and were widely celebrated, carrying out a flying tour of major US cities, listed on its flanks. It was returned to France by ship, where, by 1938 it had been donated to the museum. The story doesn't end there for the aircraft, as, some years later Costes decided that he wanted the aircraft back. His claim was based on the civil law title of Usucaption or acquisitive prescription, essentially indicating ownership or title with the passing of a period of time, but his case was rejected by the courts and the museum retained the aircraft. There was a fear by the museum staff at the time that Costes might have disposed of the airframe for self-profit. The aircraft appears imposing from its lofty perch.

Musee de l'Air 148

Musee de l'Air 148

Of course, like all the great endurance flights there were failures that littered the history of transatlantic flight. One of the most celebrated failures was that of Charles Nungesser and François Coli, who, in their white Levasseur PL.8 biplane named L'Oiseau Blanc, or The White Bird disappeared after departing Paris for New York on 8 May 1927. This is the undercarriage of the aircraft, which was discarded after take-off, landing near Gonesse to the north of Le Bourget. It is the only surviving component of the aircraft, Nungesser and Coli's fate is unknown to this day, believed lost somewhere in the Atlantic during a storm, although there are some who believe that they might have gotten as far as New Foundland and even Maine, as people reported in that they heard the aircraft flying overhead after it had been reported missing.

Musee de l'Air 150

Musee de l'Air 150

A little bit of background.

"In 1919, New York hotel owner Raymond Orteig offered the $25,000 Orteig Prize to the first aviators to make a non-stop transatlantic flight between New York and Paris in the next five years. No one won the prize, so he renewed the offer in 1924. At that point, aviation technology was more advanced and many people were working toward winning it. Most were attempting to fly from New York to Paris, but a number of French aviators planned to fly from Paris to New York.

François Coli, age 45, was a World War I veteran and recipient of the French Legion of Honor, who had been making record-breaking flights around the Mediterranean Sea and he had been planning a transatlantic flight since 1923. His original plans were to fly with his wartime comrade Paul Tarascon, a flying ace with 12 victories from the war. They became interested in the Orteig Prize in 1925, but in late 1926, an accident destroyed their Potez 25 biplane. Tarascon was badly burned and relinquished his place as pilot to 35-year-old Charles Nungesser, a highly experienced flying ace with over 40 victories, third-highest among the French. He had been planning a solo crossing to win the Orteig Prize, but designer Pierre Levasseur insisted that he consider Coli as his navigator in a new two-place variant of the Levasseur PL.4."

"Nungesser and Coli took off at 5:17 am, 8 May 1927 from Le Bourget Field in Paris, heading for New York. Their PL.8-01 weighed 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) on takeoff, extremely heavy for a single-engined aircraft, barely clearing a line of trees at the end of the field. Gathering an escort of French fighter aircraft, Nungesser and Coli turned back as planned, and at low altitude, immediately jettisoned the main undercarriage. The intended flight path was a great circle route, which would have taken them across the English Channel, over the southwestern part of England and Ireland, across the Atlantic to Newfoundland, then south over Nova Scotia, to Boston, and finally to a water landing in New York.

Once in the air, the biplane was escorted to the French coast by four military aircraft led by French Air Force Captain Venson, and sighted from the coastal town of Étretat. A sighting was made by the commanding officer of the British submarine HMS H50, who recorded the note in his log, that he observed a biplane at 300 m altitude, 20 nautical miles southwest of the tip of Needles on the Isle of Wight. In Ireland, an aircraft overhead was reported by a resident of the town of Dungarvan and a Catholic priest reported a sighting over the village of Carrigaholt, then no further verified reports were made.

Crowds of people gathered in New York to witness the historic arrival, with tens of thousands of people crowding Battery Park in Manhattan to have a good view of the Statue of Liberty, where the aircraft was scheduled to touch down. Rumors circulated that L'Oiseau Blanc had been sighted along its route, in Newfoundland, or over Long Island. In France, some newspapers even reported that Nungesser and Coli had arrived safely in New York, evoking a wave of French patriotism. L'Oiseau Blanc had been carrying a sizable load of fuel, 4,000 litres (1,100 US gal), which would have given them approximately 42 hours of flight time. After this time had passed, with no word as to the aircraft's fate, it was realized that the aircraft had been lost. In France, the public was scandalized by the newspapers such as La Presse which had printed false reports about the aircraft's arrival, and outrage was generated against the companies involved, with demonstrations in the streets."

A sad story, of which the French have reason to be proud. A model of L'Oiseau Blanc.

Musee de l'Air 149

Musee de l'Air 149

Some miscellaneous aircraft around the hall: A DH.89A Dragon Rapide used as a parachuting jump aircraft in the mid-1950s by Service de LAviation Legere Et Sportive. Originally built as HG721 for the RAF in 1945, the aircraft was registered as G-ALGB after a three-year military career before heading across the Channel for France.

Musee de l'Air 153

Musee de l'Air 153

A Caudron C.277 Luciole, or Firefly. This unassuming biplane was built in staggering numbers in the 1930s, with over 700 being completed. As with other French types, the base model was the C.270, the 277 being distinguished by its engine, a 140 hp Renault 4PE inline. A little bit of information:

"This aircraft had a huge success with more than 700 machines built base model and variants in a decade, until the Second World War. Of this production, 296 were purchased by the French Government for the training of its pilots within the framework of the Popular Aviation. Pilot and instructor Yvonne Jourjon has trained future aces of the French fighter. Several examples have been used in the military as a liaison aircraft. During general de Gaulle's dispatch to Dakar in 1940, two Firefly aircraft took off from the aircraft carrier Ark Royal and landed on the Ouakam Senegal aerodrome to install an optical signalling device after joining free France fighter group 1/4. It was a failure ː the head of GC 1/4, Commander Guy Fanneau de la Horie, and Colonel Georges Pelletier-Doisy, commander larmée de lair in Senegal, passing through the base, had the Gaullist emissaries arrested. The surviving examples of the conflict will be in great demand as glider tug planes at the École de lair in Salon-de-Provence."

From here ⓘ Caudron C.270. Le C.270 était un biplan conventionnel avec d which also describes the variants built.

Musee de l'Air 154

Musee de l'Air 154

There is so much written about the story of Henri Mignet and his home-built Pou-du-Ciel (Flying Flea), that I couldn't begin to know where to start. Basic information:

"The Flying Flea family of aircraft was designed by Frenchman Henri Mignet. Between 1920 and 1928, Mignet built various prototypes from the HM.1 to the HM.8, a monoplane that was the first of his designs that really flew. Between 1929 and 1933, he continued building prototypes, and testing them in a large field near Soissons. In 1933, Mignet successfully flew for the first time in his HM.14, the original flying flea, and publicly demonstrated it. In 1934, he published the plans and building instructions in his book Le Sport de l'Air. In 1935, it was translated into English and serialized in Practical Mechanics, prompting hundreds of people to build their own Flying Fleas. Mignet's original HM.14 prototype aircraft was powered by a 17 hp (13 kW) Aubier-Dunne 500 cc two stroke motorcycle engine. It had a wingspan of 19.5 feet (5.9 m), a length of 11.5 feet (3.5 m) and a gross weight of 450 lb (204 kg). It had a usable speed range of 25-62 mph (40â€"100 km/h). In the UK in 1935 and 1936, many aerodynamic and engine developments took place, notably by Stephen Appleby, John Carden and L.E. Baynes.

Mignet intentionally made the aircraft simple. The Flying Flea is essentially a highly staggered biplane, which almost could be considered to be a tandem wing aircraft, built of wood and fabric. The original design was a single-seater, and had two-axis flying controls. The aircraft had a standard control stick. Fore-and-aft movement controlled the front wing's angle of attack, increasing and decreasing the lift of the wing. Because the front wing was located forward of the center of gravity, that would pitch the nose up and down.

Side-to-side movement of the stick controlled the large rudder. This produced a rolling motion because the wings both had substantial dihedral, through yaw-roll coupling. The rudder had to be quite large not only to produce adequate roll but also because the fuselage was very short, reducing the leverage of the rudder. The Flying Flea, being a two-axis aircraft, could not be landed or taken off in substantial crosswinds. This was not a big issue when the aircraft was designed because at that time aircraft were usually flown from large open fields allowing all take-offs and landings into wind. Mignet claimed that anyone who could build a packing case and drive a car could fly a Flying Flea."

From here: Flea History – The Backyard Builder's Forum

The history of this particular aircraft is not known, it's not even acknowledged on the museum's website!

Musee de l'Air 155

Musee de l'Air 155

Finally for today, the awesome Breguet Bugatti 32b Quadimoteur! I will refer you to this extensively detailed article on this engine collaboration for further information; I was going to copy it at any rate, so I might as well just link to the page: January 2015 – Old Machine Press

Musee de l'Air 156

Musee de l'Air 156

More to come...

So, we continue with this fuselage section of a Farman F.60 Goliath airliner, a pioneering type that saw service throughout the 20s but began life as a bomber in 1918. Here's some information about it from the usual source:

"The Goliath was initially designed in 1918 as a heavy bomber capable of carrying 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) of bombs with a range of 1,500 km (930 mi). It was a fixed-undercarriage three-bay biplane of fabric-covered wood construction, powered by two Salmson 9Z engines. It had a simple and robust, yet light structure. The wings were rectangular with a constant profile with aerodynamically balanced ailerons fitted to both upper and lower wings.

It was undergoing initial testing when World War I came to an end and Farman realized there would be no orders for his design. Nonetheless he was quick to understand that the big, box-like fuselage of the Goliath could be easily modified to convert the aircraft into an airliner. Commercial aviation was beginning to be developed and was in need of purpose-built aircraft. With the new passenger cabin arrangement, the Goliath could carry up to 12 or 14 passengers. It had large windows to give the passengers a view of the surroundings. The Salmson engines could be replaced by other types (Renault, Lorraine) if a customer desired it. Approximately 60 F.60 Goliaths were built. Between 1927 and 1929, eight Goliaths with various engines were built under licence in Czechoslovakia, four by Avia and four by Letov."

The history of the Goliath is fascinating and although only 60 were built the type was operated by lots of different airlines around the world, but it suffered a high accident rate. This particular example, F-HMFU, was employed by Air Union as Île de France between Paris and London (Croydon), but in October 1925 it suffered a crash in East Sussex, resulting in the deaths of three passengers and the injuring of two more. It remained registered until 1932 and the fuselage was recovered, but the aircraft never flew again. It is the only surviving section of a Goliath airliner.

This next aircraft is one of the three most important aircraft in the museum's collection, according to the website. It is of course the striking red Breguet XIX TF Super Bidon Point d'Interrogation, or simply "?". Following from Charles Lindberg's historic solo Atlantic Crossing in 1927, On 1 September 1930, Captain Dieudonne Costes and Navigator Maurice Bellonte took off from Le Bourget, beginning their transatlantic crossing, arriving in the United States at Curtiss Field, New York on the 3rd, after a 37-hour 12-minute flight that covered 3850 miles. Lindberg was there to meet the two Frenchmen. A significant feat, as owing to the prevailing winds, an east-to-west aerial crossing is eminently more difficult; the first being by the rigid airship R.34, a mere two weeks after John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown's Atlantic crossing in a Vickers Vimy in June 1919. The Super Bidon wasn't the first aeroplane to make the crossing in a westerly direction, in 1928 the Junkers W 33L D 1167 Bremen, piloted by Hermann Koehl, with Baron Gunther von Huenefeld and Commandant James Fitzmaurice aboard became the first, flying between Baldonnel, near Dublin and New Foundland. The Super Bidon in its cherry red colour scheme, sitting on top of a display about transatlantic crossings by air.

First flying on 23 July 1928, the Point d'Interrogation was the last of three TR, or Transatlantique variants built, but it was converted into a TF Super Bidon, which involved numerous modifications, including extending the wingspan, lengthening the fuselage and installing increased fuel tankage. Undertaking sponsorship from Hispano-Suiza, the aircraft's engine manufacturer, the aircraft's manufacturer Breguet and an anonymous benefactor, Costes and Bellonte began preparations for an Atlantic crossing from Paris in 1929. Adorning the aircraft was a white question mark, a nod to the anonymous benefactor, which it became known for, as well as the stork insignia of the Escadrille des Cigognes of Great War fame, which conveniently served as the emblem of Hispano-Suiza. Taking off on 13 July, bad weather hampered the flight on the southern route via the Azores and after covering 1600 miles, Costes elected to return to Paris, not wishing to risk the deteriorating conditions. To maintain the support of their sponsors the duo flew a number of record-breaking flights following their first aborted Atlantic crossing, which included a flight from Paris to Moullart in Manchuria, a journey of 4319 miles in September 1929. A number of circular endurance flights were also flown before the pair and their bright red biplane set off across the Atlantic for a second time. These are recorded on the aircraft's flanks. The mysterious benefactor from whence came its name? The perfume maker Coty!

Their next attempt was to be made only if the weather was favourable and an agent from the French meteorological office kept a close eye on the weather prior to the flight, enabling a successful crossing in September 1930. Powered by a 650 hp Hispano-Suiza 12Nb engine, the aircrew sat in open cockpits with shielding but were entirely exposed during the flight. Costes' instrumentation was typical of the period, being very crude, with a minimum of dials, dominated by a big compass directly in front of him. After landing in New York, Costes and Bellonte received a ticker-tape parade and were widely celebrated, carrying out a flying tour of major US cities, listed on its flanks. It was returned to France by ship, where, by 1938 it had been donated to the museum. The story doesn't end there for the aircraft, as, some years later Costes decided that he wanted the aircraft back. His claim was based on the civil law title of Usucaption or acquisitive prescription, essentially indicating ownership or title with the passing of a period of time, but his case was rejected by the courts and the museum retained the aircraft. There was a fear by the museum staff at the time that Costes might have disposed of the airframe for self-profit. The aircraft appears imposing from its lofty perch.

Of course, like all the great endurance flights there were failures that littered the history of transatlantic flight. One of the most celebrated failures was that of Charles Nungesser and François Coli, who, in their white Levasseur PL.8 biplane named L'Oiseau Blanc, or The White Bird disappeared after departing Paris for New York on 8 May 1927. This is the undercarriage of the aircraft, which was discarded after take-off, landing near Gonesse to the north of Le Bourget. It is the only surviving component of the aircraft, Nungesser and Coli's fate is unknown to this day, believed lost somewhere in the Atlantic during a storm, although there are some who believe that they might have gotten as far as New Foundland and even Maine, as people reported in that they heard the aircraft flying overhead after it had been reported missing.

A little bit of background.

"In 1919, New York hotel owner Raymond Orteig offered the $25,000 Orteig Prize to the first aviators to make a non-stop transatlantic flight between New York and Paris in the next five years. No one won the prize, so he renewed the offer in 1924. At that point, aviation technology was more advanced and many people were working toward winning it. Most were attempting to fly from New York to Paris, but a number of French aviators planned to fly from Paris to New York.

François Coli, age 45, was a World War I veteran and recipient of the French Legion of Honor, who had been making record-breaking flights around the Mediterranean Sea and he had been planning a transatlantic flight since 1923. His original plans were to fly with his wartime comrade Paul Tarascon, a flying ace with 12 victories from the war. They became interested in the Orteig Prize in 1925, but in late 1926, an accident destroyed their Potez 25 biplane. Tarascon was badly burned and relinquished his place as pilot to 35-year-old Charles Nungesser, a highly experienced flying ace with over 40 victories, third-highest among the French. He had been planning a solo crossing to win the Orteig Prize, but designer Pierre Levasseur insisted that he consider Coli as his navigator in a new two-place variant of the Levasseur PL.4."

"Nungesser and Coli took off at 5:17 am, 8 May 1927 from Le Bourget Field in Paris, heading for New York. Their PL.8-01 weighed 5,000 kg (11,000 lb) on takeoff, extremely heavy for a single-engined aircraft, barely clearing a line of trees at the end of the field. Gathering an escort of French fighter aircraft, Nungesser and Coli turned back as planned, and at low altitude, immediately jettisoned the main undercarriage. The intended flight path was a great circle route, which would have taken them across the English Channel, over the southwestern part of England and Ireland, across the Atlantic to Newfoundland, then south over Nova Scotia, to Boston, and finally to a water landing in New York.

Once in the air, the biplane was escorted to the French coast by four military aircraft led by French Air Force Captain Venson, and sighted from the coastal town of Étretat. A sighting was made by the commanding officer of the British submarine HMS H50, who recorded the note in his log, that he observed a biplane at 300 m altitude, 20 nautical miles southwest of the tip of Needles on the Isle of Wight. In Ireland, an aircraft overhead was reported by a resident of the town of Dungarvan and a Catholic priest reported a sighting over the village of Carrigaholt, then no further verified reports were made.

Crowds of people gathered in New York to witness the historic arrival, with tens of thousands of people crowding Battery Park in Manhattan to have a good view of the Statue of Liberty, where the aircraft was scheduled to touch down. Rumors circulated that L'Oiseau Blanc had been sighted along its route, in Newfoundland, or over Long Island. In France, some newspapers even reported that Nungesser and Coli had arrived safely in New York, evoking a wave of French patriotism. L'Oiseau Blanc had been carrying a sizable load of fuel, 4,000 litres (1,100 US gal), which would have given them approximately 42 hours of flight time. After this time had passed, with no word as to the aircraft's fate, it was realized that the aircraft had been lost. In France, the public was scandalized by the newspapers such as La Presse which had printed false reports about the aircraft's arrival, and outrage was generated against the companies involved, with demonstrations in the streets."

A sad story, of which the French have reason to be proud. A model of L'Oiseau Blanc.

Some miscellaneous aircraft around the hall: A DH.89A Dragon Rapide used as a parachuting jump aircraft in the mid-1950s by Service de LAviation Legere Et Sportive. Originally built as HG721 for the RAF in 1945, the aircraft was registered as G-ALGB after a three-year military career before heading across the Channel for France.

A Caudron C.277 Luciole, or Firefly. This unassuming biplane was built in staggering numbers in the 1930s, with over 700 being completed. As with other French types, the base model was the C.270, the 277 being distinguished by its engine, a 140 hp Renault 4PE inline. A little bit of information:

"This aircraft had a huge success with more than 700 machines built base model and variants in a decade, until the Second World War. Of this production, 296 were purchased by the French Government for the training of its pilots within the framework of the Popular Aviation. Pilot and instructor Yvonne Jourjon has trained future aces of the French fighter. Several examples have been used in the military as a liaison aircraft. During general de Gaulle's dispatch to Dakar in 1940, two Firefly aircraft took off from the aircraft carrier Ark Royal and landed on the Ouakam Senegal aerodrome to install an optical signalling device after joining free France fighter group 1/4. It was a failure ː the head of GC 1/4, Commander Guy Fanneau de la Horie, and Colonel Georges Pelletier-Doisy, commander larmée de lair in Senegal, passing through the base, had the Gaullist emissaries arrested. The surviving examples of the conflict will be in great demand as glider tug planes at the École de lair in Salon-de-Provence."

From here ⓘ Caudron C.270. Le C.270 était un biplan conventionnel avec d which also describes the variants built.

There is so much written about the story of Henri Mignet and his home-built Pou-du-Ciel (Flying Flea), that I couldn't begin to know where to start. Basic information:

"The Flying Flea family of aircraft was designed by Frenchman Henri Mignet. Between 1920 and 1928, Mignet built various prototypes from the HM.1 to the HM.8, a monoplane that was the first of his designs that really flew. Between 1929 and 1933, he continued building prototypes, and testing them in a large field near Soissons. In 1933, Mignet successfully flew for the first time in his HM.14, the original flying flea, and publicly demonstrated it. In 1934, he published the plans and building instructions in his book Le Sport de l'Air. In 1935, it was translated into English and serialized in Practical Mechanics, prompting hundreds of people to build their own Flying Fleas. Mignet's original HM.14 prototype aircraft was powered by a 17 hp (13 kW) Aubier-Dunne 500 cc two stroke motorcycle engine. It had a wingspan of 19.5 feet (5.9 m), a length of 11.5 feet (3.5 m) and a gross weight of 450 lb (204 kg). It had a usable speed range of 25-62 mph (40â€"100 km/h). In the UK in 1935 and 1936, many aerodynamic and engine developments took place, notably by Stephen Appleby, John Carden and L.E. Baynes.

Mignet intentionally made the aircraft simple. The Flying Flea is essentially a highly staggered biplane, which almost could be considered to be a tandem wing aircraft, built of wood and fabric. The original design was a single-seater, and had two-axis flying controls. The aircraft had a standard control stick. Fore-and-aft movement controlled the front wing's angle of attack, increasing and decreasing the lift of the wing. Because the front wing was located forward of the center of gravity, that would pitch the nose up and down.

Side-to-side movement of the stick controlled the large rudder. This produced a rolling motion because the wings both had substantial dihedral, through yaw-roll coupling. The rudder had to be quite large not only to produce adequate roll but also because the fuselage was very short, reducing the leverage of the rudder. The Flying Flea, being a two-axis aircraft, could not be landed or taken off in substantial crosswinds. This was not a big issue when the aircraft was designed because at that time aircraft were usually flown from large open fields allowing all take-offs and landings into wind. Mignet claimed that anyone who could build a packing case and drive a car could fly a Flying Flea."

From here: Flea History – The Backyard Builder's Forum

The history of this particular aircraft is not known, it's not even acknowledged on the museum's website!

Finally for today, the awesome Breguet Bugatti 32b Quadimoteur! I will refer you to this extensively detailed article on this engine collaboration for further information; I was going to copy it at any rate, so I might as well just link to the page: January 2015 – Old Machine Press

More to come...

great stuff Grant

Lovely shots Grant!

- Thread starter

- #72

...And so we continue on this detailed look at the exhibits at one of the finest aviation collections in the world. It does take time to put these together, hence the infrequent posts. Also, I have had assignments to hand in, so that doesn't help.

Our next aeroplane is the pretty if functional Caudron C.630 Simoun. This aeroplane is constructor's serial No.428, but is represented as No.19 F-ANRO in the colours of Air Bleu, which was a mail transport concern that had six Simouns delivering post to airports around France, transporting around 45 million letters in a two year period, with very high reliability for the time.

Musee de l'Air 151

Musee de l'Air 151

A bit about the sleek monoplane from this excellent site on the reconstruction of a surviving example: Avion Collection | Projet de Renaissance du Caudron Simoun

"The CAUDRON SIMOUN was designed by Marcel RIFFARD, with the collaboration of the engineer OFTINOVSKI in order to participate in the 4th international tourism challenge held in Poland from August 28 to September 16, 1934.

To have a chance of winning this trophy, the planes had to be low-wing monoplanes with closed cabins; have an unladen weight of 560 Kg maximum, a minimum speed of 75 Km/hour, a range of 600 Km, a take-off and landing distance of less than 100 m The retractable gear did not bring additional points contrario of the capacity, sorting or better the four-seater was therefore the rule.

The French Ministry of Air, under the direction of Pierre COT, decided in 1933 to improve France's results in this event, which had not been very brilliant in previous years. He placed an order with CAUDRON-RENAULT (which knew how to build fast aircraft, especially for the Deutsch de la Meurthe Cup), for a C500 that he thought could win the competition.

At the beginning of 1934 was therefore launched in Issy-les-Moulineaux, under the direction of Marcel RIFFARD, the manufacture of eight C500 intended to receive registrations from F-ANCA to F-ANCH, but at that time the priority went to the C366 Atalante, C450, C460 and C530 Rafale for the Deutsch de la Meurthe cup. On the first registration date, April 17, only three aircraft will be able to be registered, three others will be registered thereafter, which will limit the number of CAUDRON-RENAULT participants.

The production of C500 number 1 (n/c 6952) Simoun IV in Guyancourt was limited to three.

To make matter worse, it was noticed in mid-August 1934 that the first example was too heavy by 60 kilos. This overweight was due to various devices (flaps and wing folding system) and it was then decided to replace the RENAULT Bengali 6Pfi engine of 170 hp by a RENAULT Bengali 4 Pei less powerful but lighter (minus 50 kg), this resulting in a modification of the airframe.

These modifications involve work carried out day and night so that at least two first copies (n/c 6951 and 6952) are completed on time. Despite this, France announced, on the morning of August 24, 1934, its package for this challenge.

Despite this mishap, the C500 did not disappear. The disappointment passed, the development of the prototypes resumes, without worries of delay, nor weight limitation. If the first example keeps its RENAULT 4 Pei, the second finds a RENAULT 6 Pfi.

The tests conducted by Raymond DELMOTTE in Guyancourt show that the aircraft has remarkable performance in its category.

His future was assured when Beppo de MASSIMI and his friend Didier DAURAT obtained the financial support of Louis RENAULT for the launch of the company AIR BLEU, operating a new air mail network. The C500, which was presented to them on October 3, 1934, seemed quite suitable, subject to some modifications. It was in November 1934, that the aircraft was presented at the XIV Paris Air Show.

Nicknamed the "Viva Grand Sport des Airs" or the "Limousine de l'air" in reference to the RENAULT car model, it is offered in two versions: the C500 Simoun IV equipped with a RENAULT 4Pdi engine of 4 cylinders of 140/150 hp and the C520 Simoun VI equipped with the RENAULT "Bengali six" 6Q 06 of 6 cylinders of 170/195 hp. It is the C520 that will become the C620, then the C630 after modification of the fuselage."

Musee de l'Air 158

Musee de l'Air 158

Our next machine is the very pretty Potez 53 racing aeroplane built specifically for the prestigious 1933 Deutsch de la Meurthe Cup, which it succeeded in triumphing in, piloted by Georges Détré on 29 May 1933. Here's a bit of background to the race (I'll place the source at the bottom of the two posts on the aircraft since its lengthy and detailed):

"Born in 1846 in Paris, Henry Deutsch de la Meurthe was an industrialist in the field of hydrocarbons. Passionate about aviation, he was one of the founding members, in 1898, of the Aéro-Club de France. He will become its president.

In April 1900, he created a prize of 100,000 francs (gold) for the one who, before October 1904, would be the first able to make the round trip between Saint-Cloud and the Eiffel Tower in less than 30 minutes. This prize will be won by Santos-Dumont, aboard his airship n°6, in September 1901, with a controversy as to the duration of the flight which would be 29 minutes for some and 32 for others.

It was in 1904 that he proposed, with his friend Ernest Archdeacon, a prize of 50,000 gold francs for the aviator who had succeeded first, one kilometer in a closed circuit, with return to his starting point; we can say by this that they are a little at the origin of the exploit of Henry Farman, commented at length in the Pegasus n °126 of March 2008.

With the progress of aviation, many competitions, and in particular speed races, are organized under the aegis of the Aéro-Club de France and its president. Interrupted by the war, they resumed in 1919. The latest saw the victory of Sadi-Lecointe in a two-time 200 km race run on 2 September 1919 and 24 January 1920, aboard a Nieuport 29 equipped with a Hispano-Suiza engine of 300 hp, at an average of 266.11 km/h.

On November 24, 1919, at the age of 73, Henry Deutsch de la Meurthe died in Ecquevilly, in the Seine-et-Oise (now Yvelines department)."

"His daughter Suzanne (1892–1937), in partnership with the Aéro-Club de France, which wanted to pay tribute to its late president, set up a speed race. The first lines of the regulation are as follows: "In memory of Mr. Henry Deutsch de la Meurthe, Mrs. Henry Deutsch de la Meurthe and her children have decided to devote a sum of 200,000 F to an international speed event to be called the Henry Deutsch de la Meurthe Cup."

The regulations provide that this cup will be played every year, so in principle, for three years. It is the National Federations that are entering the race. They designate one or more competitors who will be their representatives; they must belong to the nationality of the Federation that presents them.

The 200,000 F offered are distributed as follows: 60,000 F in cash for each of the winners of the three races. In addition, an art object worth 20,000 F will be given to them as a trophy; the National Federation, whose representative won the race, will be the holder until the next award. The final holder of the cup will be the competitor who won the event twice, or, failing that, the third winner. (These are, of course, the aeronautical firms, because the pilots who are their employees race on their behalf)."

Musee de l'Air 144

Musee de l'Air 144

For a 1933 aeroplane, the Potez is of remarkably advanced streamlined form. Constructed primarily of plywood, the aircraft is designed as small as possible to match the dimensions and power output of its 9B single-row nine cylinder supercharged radial engine capable of producing 310 hp and driving a metal fixed pitch propeller. Even the cockpit was tailor made in size to conform to the physical size of its pilots, the degree to which Potez wished to improve its power-to-weight ratio. Of small dimensions, over 17 feet long, with a 21 foot wingspan and weighing only 1,900 lbs fully loaded, it was fitted with fully retractable undercarriage, which retracted outwards from the fuselage into the wings, offering a narrow track, with a tail skid. Instrumentation in the cockpit was rudimentary conforming to the needs of a strictly racing aeroplane.

Here's some more on the race itself that the Potez won:

"The big day of May 28 arrives. Of course, the weather is bad and the event is postponed to the next day, May 29. Thirteen candidates registered for the race. They have been assigned, by lot, a serial number that must be written in large white numbers on the fuselages. Georges Détré's plane receives the number 10 and that of Gustave Lemoine, the number 12.

"For various reasons that it would be tedious to list (let us mention, however, the death of Captain Ludovic Arachart who killed himself, on May 24, while carrying out the tests of the Caudron n ° 11), there are only six planes left, at the start, on the 29th in the morning. Maurice Arnoux's Renault-powered Farman aircraft rolls a hundred meters, breaks its single-wheel lander, damages its propeller and is forced to give up. In the end, only five aircraft took part in the 1933 Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe.

"Gustave Lemoine, on his n°12 takes off at 10:10 in 40 seconds (believe me, he must have found the time long, because it represents a good kilometer of rolling, if not more; the other planes took off in 15 or 20 seconds). Chief test driver of the firm Potez, it was obviously he who had the mission to win the race by making the most of his engine; but in his first lap of the circuit, hampered by poor visibility, he lacks control of Ormoy and loses some 25 minutes (that the drivers who have never strayed throw him the first stone: it will certainly not be me). The race is over for him. He will nevertheless run three additional laps of the circuit: lap 2 will be carried out at an average speed of 354.7 km/h, the n°3 at 352.9 km/h and the n°4 at 356.1 km/h. He broke the lap record twice. He landed at the end of his fourth lap, officially because he had consumed enough gas to lighten his aircraft and his engine was starting to heat up, but, the bad tongues say that it was mainly because it was lunchtime.

"Georges Détré, whose mission was to ensure the blow by making a waiting race while sparing his engine, took off at 10:05. He only drove for 35 seconds, because the propeller of the 3402, slightly larger than that of the 3403, was to favor the take-off of the plane, but it must also be believed that the strength and direction of the wind were more favorable for him than they will be for Lemoine, five minutes later.

"A few days before the race, aboard a Potez 36, Georges Détré, out of caution, had made a precise reconnaissance of the race route. In addition, on the morning of May 29, still on his Potez 36, he had ensured the good atmospheric conditions throughout the course. He thus had no navigation problems and was able to devote himself exclusively to driving his small car.

"Everything, for him, then takes place in a simple and regular way, I would say almost monotonous. To take his turns without losing speed, especially that of Etampes which is very tight, he prefers to fly a few distances outside the officially chosen route (the method to make a change of direction, in a minimum of time, normally taught in hunting schools is this: once past the line of control, perform a candle climb, then tilt 80/90 degrees. Keeping the depth neutral, the nose of the aircraft falls back on the horizon. After turning into a handkerchief, the aircraft resumes all its speed in the dive following this maneuver. It is clear that the Potez 53 did not allow such a fantasy and, without demanding too much from its engine, it runs regularly, slightly above 320 km/h per lap. He completed his best lap, the tenth of the first round, at 329.4 km/h. The first thousand kilometers are covered in 3 hours 05 minutes and 45 seconds. After the obligatory stop of an hour and a half, the second round took place without incident and Georges Détré, aboard the Potez 53 n°10, won the Coupe Deutsch de la Meurthe 1933 in 6 hours 11 minutes and 45 seconds, at an average hourly speed of 322.8 km/h."

From here: LE POTEZ 53

Following its victory, Henri Potez donated the slick little aircraft to the museum.

Musee de l'Air 159

Musee de l'Air 159

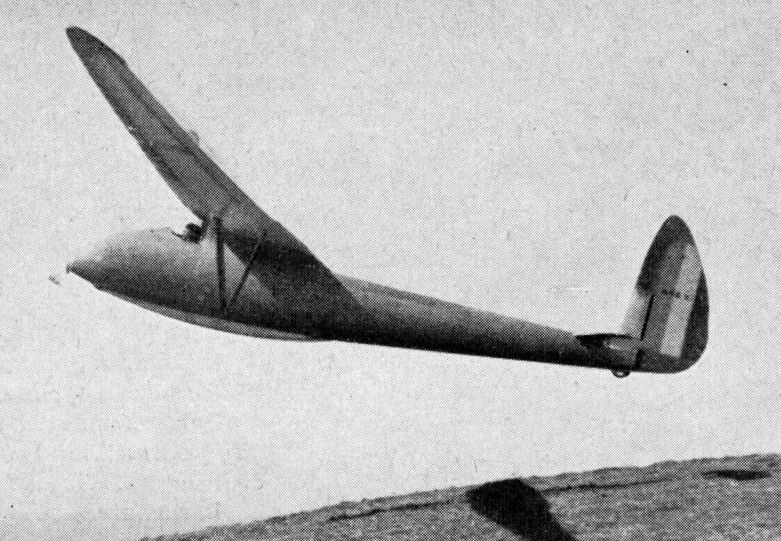

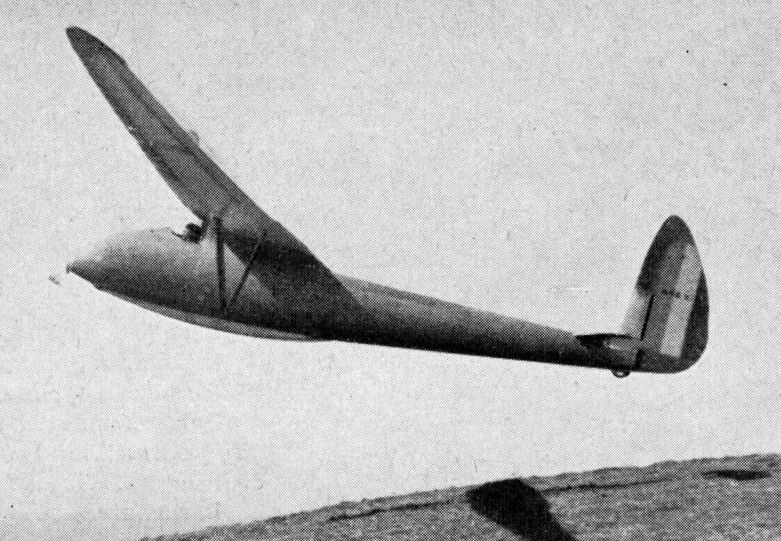

Next, the very simple yet effective planforms of the Schulgleiter SG.38, which was initially designed by Edmund Schneider, Rehberg and Hofmann at Schneider's factory at Grunau in 1938, although German aeronautical legend Alexander Lippisch is credited with contributing research to the type. Lippisch was of course later responsible for the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet's somewhat unique configuration and saw employment with Convair in the United States in researching supersonic interceptors, which is outside the scope of this thread, being quite far removed from these elementary training gliders. The foreground SG.38 represents the basic form that the majority of the type were built as, which a firm number constructed is not known but is estimated at around 10,000 with construction in Britain, Japan and Spain, contributing to the wave of interest in segelflug in Nazi Germany which culminated in the sport becoming the demonstration favourite during the 1936 XI Olympiade in Berlin, with also the small matter of the foundation of the pilots that formed the bulk of the new Nazi Luftwaffe being credited to tuition on the SG.38... The background glider differs from the foreground in having a streamlined casing for the pilot, but differs little in detail.

Musee de l'Air 161

Musee de l'Air 161

We stay with segelflug and the Avia 41p record breaking glider. This particular aircraft was built by Ateliers vosgiens d'industrie aéronautique, or Avia and was based on the German Lippisch Wien glider, there's our man Lippisch again, which first flew in 1929. The Avia examples were built two years later and set about claiming various French and world gliding records over the next few years before the outbreak of World War Two. This one, No.3 while flown by Lt Wermert covered a distance of 207 kilometres at an altitude of 1,850 metres (over 6,000 feet) on 17 September 1936. Wikipedia gives a good description of the Avia 41p:

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org