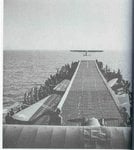

Ran across this picture published by the Center of Military History of the US Army in the book called the War in the Mediterranean.

I was surpised how short of runway a L-4 needs to take off. They where used for direction of Naval Artillery and had to land on the Anzio beaches due to the fact they couldnt land back on board the LST carrier.

Does any one have any idea what unit these aircraft belong to or any more pictures that show the side of the ship with the aircraft on board.

Thanks Micdrow

I was surpised how short of runway a L-4 needs to take off. They where used for direction of Naval Artillery and had to land on the Anzio beaches due to the fact they couldnt land back on board the LST carrier.

Does any one have any idea what unit these aircraft belong to or any more pictures that show the side of the ship with the aircraft on board.

Thanks Micdrow