The Lycoming IO-360 makes 200hp in certified form, which gives 0.55 hp/ci (up to 220hp for experimental: 0.65 hp/ci). Gives some idea of what modern aircraft engines are giving out.Modern gasoline radials aren't even close. The Rotec 9-cylinder radial is 220 cubic inches and makes 150 HP for 0.68 HP/cubic inch. The Vedeneyev M-14-P has 9 cylinders, 621 cubic inches, and makes 400 HP for .644 HP/cubic inch. These are very reliable and desirable engines for aerobatic aircraft. They now come with either air-start or electric start as an option. One reason they aren't as close to the magic 1 hp/cubic inch is we are limited to about 100-Octane LL fuel today. There isn't any 145 / 150 PN leaded fuel around except in special batches sometimes made for the Reno air races and whatever brews are made up in private hangars.

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Large Radial Engines Were About As Good As Can Be? (2 Viewers)

- Thread starter kitplane01

- Start date

Ad: This forum contains affiliate links to products on Amazon and eBay. More information in Terms and rules

More options

Who Replied?Shortround6

Lieutenant General

Lycoming got up to 0.71hp/ci back in the 50s on a supercharged (mechanical) geared 480 cu in engine (340hp from take-off to 8,000ft) using 100/130 fuel and 9lb of boost.

There were a few other models/sizes of supercharged/geared engines.

They went away when they found that engines with more displacement per cylinder could make the same or similar amounts of power while running slower and not needing the reduction gear and/or supercharger. The larger engines lasted longer between overhauls and without superchargers and reduction gears they were cheaper to overhaul.

The gas turbines killed the supercharged high rpm flat six/flat eight market.

A lot of things affect engine choice in the light airplane market. HP per cubic inch is way down on the list. somewhere about paint color on the engine block

There were a few other models/sizes of supercharged/geared engines.

They went away when they found that engines with more displacement per cylinder could make the same or similar amounts of power while running slower and not needing the reduction gear and/or supercharger. The larger engines lasted longer between overhauls and without superchargers and reduction gears they were cheaper to overhaul.

The gas turbines killed the supercharged high rpm flat six/flat eight market.

A lot of things affect engine choice in the light airplane market. HP per cubic inch is way down on the list. somewhere about paint color on the engine block

Deleted member 68059

Staff Sergeant

- 1,056

- Dec 28, 2015

="The kommandogerat is a tinkertoy compared to the mechanical control systems you can rustle up now."

In what way?

Other than being instantly programmable (i.e. being altered in 5seconds instead of needing a new cam ground) it does exactly the same thing.

It allows ignition timing, boost and fuel to be altered on the basis of inputs of temperture, pressure, and load. Most WW2 engines were NOT limited in performance

by virtue of over simplified control systems. They were limited by all the fundamental physics that wasnt yet sorted out, mostly combustion system

understanding.

All the tiny tweaking of transient performance is meaningless in a virtually constant speed engine like aero-engines.

The engines in the lab in 1940 were instrumented to similar degrees as they are now, cylinder pressure, EGT, exhaust gas analysis, albeit very laboriously and without nice logging, but the kommandogerats (etc) were not fred flintstone items and although of course you`d chuck them in the bin now, throwing them away will only gain you convenience not performance.

Last edited:

Reliability is a lot of what killed the GO-480. I haven't heard much good ever said about them.Lycoming got up to 0.71hp/ci back in the 50s on a supercharged (mechanical) geared 480 cu in engine (340hp from take-off to 8,000ft) using 100/130 fuel and 9lb of boost.

There were a few other models/sizes of supercharged/geared engines.

They went away when they found that engines with more displacement per cylinder could make the same or similar amounts of power while running slower and not needing the reduction gear and/or supercharger. The larger engines lasted longer between overhauls and without superchargers and reduction gears they were cheaper to overhaul.

The gas turbines killed the supercharged high rpm flat six/flat eight market.

A lot of things affect engine choice in the light airplane market. HP per cubic inch is way down on the list. somewhere about paint color on the engine block

A much longer-lived geared engine the continental GO-300 makes 175 hp, which equates to 0.58.

For an air-cooled piston engine, displacement directly relates to surface area and cooling efficiency, so its not entirely irrelevant. It looks like somewhere around 0.6 is around the sweet spot for reliability, for the tech of the time.

Gas turbines killed off the high Hp piston engine market. They still can't really compete under about 300Hp.

swampyankee

Chief Master Sergeant

- 4,152

- Jun 25, 2013

What is truly amazing is not that we can do better now, but that they were building hundreds or thousands of engines per month that were equivalent in HP to weight and fit and finish to the race car engine of the 1960s which were never built in anywhere near those quantities ( 25 engines a year might be high production for a race car engine)

People underestimate how good piston aircraft engines were and even are compared to race car engines. While I don't think radials were as good as they could be, they were as good as they could be within the technological and economic constraints in force at the time. Now, of course, an ab initio piston aircraft engine of over a few dozen horsepower would probably be a diesel (avgas is nearly unavailable in many parts of the world).

Using modern design technology but 1945 materials for a radial would likely permit a far better supercharging system (two stage turbocharging, perhaps?) and greater compression ratios with the fuels of the era (or lower performance number fuels for the same compression ratio), lower sfcs, and less structural weight.

Shortround6

Lieutenant General

I sure don't know enough but as always, there are a bunch of trade-offs. Wright and P & W both used hemi heads (or darn close to it) with pushrods and spark plugs near the center of the head, one plug on each side of the valves. there are certainly a lot more sophisticated head designs and valve arrangements BUT.......................

Does the more sophisticated valve arrangement weigh more?

Does the more sophisticated valve arrangement require more volume/increase diameter?

Does the more sophisticated valve arrangement cost more?

Does the more sophisticated valve arrangement take up valuable real estate that could be used for cooling fins?

Does the more sophisticated valve arrangement actually allow the engine to turn more rpm or is the rpm limit restriction due to the bottom end?

There may be more. Please note that some of these considerations conflict with each other, A radial engine using high boost needs a high octane fuel, It also needs a lot of cooling fin area. If you use a valve arrangement that cuts down on the cooling fins you may not be able to use as much boost which requires higher rpm for the same power (except you still have to get rid of the heat.) and similar tail chases.

The amount of cylinder finning is going to directly affect how much power you can make in each cylinder regardless of how it is made. Fans may help (but if the plane is cruising at 300mph needing a fan seems ridiculous) but they require power and maintenance.

Modern technology can do a lot but lets look at the goals they were meeting and how it was done.

Does the more sophisticated valve arrangement weigh more?

Does the more sophisticated valve arrangement require more volume/increase diameter?

Does the more sophisticated valve arrangement cost more?

Does the more sophisticated valve arrangement take up valuable real estate that could be used for cooling fins?

Does the more sophisticated valve arrangement actually allow the engine to turn more rpm or is the rpm limit restriction due to the bottom end?

There may be more. Please note that some of these considerations conflict with each other, A radial engine using high boost needs a high octane fuel, It also needs a lot of cooling fin area. If you use a valve arrangement that cuts down on the cooling fins you may not be able to use as much boost which requires higher rpm for the same power (except you still have to get rid of the heat.) and similar tail chases.

The amount of cylinder finning is going to directly affect how much power you can make in each cylinder regardless of how it is made. Fans may help (but if the plane is cruising at 300mph needing a fan seems ridiculous) but they require power and maintenance.

Modern technology can do a lot but lets look at the goals they were meeting and how it was done.

WW2 piston engines were clearly capable of further improvement and some lateral thinking in the day.

Here are several of the technologies that are common today that could have been introduced in the early 40s.

1 Variable Length Intake Ports. The From the DB601E Daimler Benz Introduced a radical valve overlap to resonance scavenge the cylinder head of end gasses and pressurise it by placing an node there. The variable length was necessary to ensure the engine idled and started smoothly. Direct in cylinder injection prevented fuel loss.

It should be noted that the excuse given for Rolls Royce not introducing this system that it would give up the charge cooling effect of injecting the fuel into the supercharger (precooling it) was overcome in the BMW801D2 from late 1943 onwards when 'rich mixture' injection was introduced to provide emergency power by injecting the fuel into the eye of the supercharged during WEP.

2 Variable Valve Timing. The BMW802 18 cylinder radial was to be available with variable valve timing on the exhaust. This achieves the same effect as changing the inlet manifold length. Engines like the R3350 needed fuel injection anyway due to the fuel distribution and fractionating issues they faced.

So the above are clearly possible but never applied to allied engines.

3 Knock sensors. This can be implemented in and around WW2. The older Waukesha CFR test engine simply used a pin that bounced up and down when knock was detected. It was visually extremely obvious. This itself could be used to drive a small electrical motor to advance or retard the ignition. A knock sensor is really just a microphone/accelerometer.

Knock sensors could be introduced to retard ignition (with an electrical motor) when knock is detected and if a 10% retardation of ignition doesn't stop the knock the boost can be reduced.

This allow the engine to operate with much higher boost settings or delivered with higher compression ratios that could otherwise be risked given the dangers of unusual hot condition or variable fuel quality. This appears to have been part of the problem the Germans suffered with the DB605A in raising boost from 1.3 to 1.42 ata and again from 1.8 to 1.98 ata.

Thermionic Vacuum Tubes (Valves if your British) were well up to the task. If operating at audio frequencies (not VHF/UHF) the valve could easily last 30,000-50,000 hours and handle 60G acceleration. They would be quite suitable. I don't think they'd actually be needed.

4 The Lambda Probe Oxygen Sensor is attributed to Robert Bosch GmbH during the late 1960s under the supervision of Dr. Günter Bauman. Im not sure if there was an equal sensor possible at the time, but I think there probably was. It would be useful for the kind of 2 stroke engines people were working on and indeed I see no problem incorporating it with the controls of the day. I'm just not sure if there was such a device in existence.

Personally I think had it not been for the jet engines 2 stroked turbo supercharged disels were the future. They stood a chance of actually producing 4000hp on 12-16 cylinder instead of 24,28 or 36.

Here are several of the technologies that are common today that could have been introduced in the early 40s.

1 Variable Length Intake Ports. The From the DB601E Daimler Benz Introduced a radical valve overlap to resonance scavenge the cylinder head of end gasses and pressurise it by placing an node there. The variable length was necessary to ensure the engine idled and started smoothly. Direct in cylinder injection prevented fuel loss.

It should be noted that the excuse given for Rolls Royce not introducing this system that it would give up the charge cooling effect of injecting the fuel into the supercharger (precooling it) was overcome in the BMW801D2 from late 1943 onwards when 'rich mixture' injection was introduced to provide emergency power by injecting the fuel into the eye of the supercharged during WEP.

2 Variable Valve Timing. The BMW802 18 cylinder radial was to be available with variable valve timing on the exhaust. This achieves the same effect as changing the inlet manifold length. Engines like the R3350 needed fuel injection anyway due to the fuel distribution and fractionating issues they faced.

So the above are clearly possible but never applied to allied engines.

3 Knock sensors. This can be implemented in and around WW2. The older Waukesha CFR test engine simply used a pin that bounced up and down when knock was detected. It was visually extremely obvious. This itself could be used to drive a small electrical motor to advance or retard the ignition. A knock sensor is really just a microphone/accelerometer.

Knock sensors could be introduced to retard ignition (with an electrical motor) when knock is detected and if a 10% retardation of ignition doesn't stop the knock the boost can be reduced.

This allow the engine to operate with much higher boost settings or delivered with higher compression ratios that could otherwise be risked given the dangers of unusual hot condition or variable fuel quality. This appears to have been part of the problem the Germans suffered with the DB605A in raising boost from 1.3 to 1.42 ata and again from 1.8 to 1.98 ata.

Thermionic Vacuum Tubes (Valves if your British) were well up to the task. If operating at audio frequencies (not VHF/UHF) the valve could easily last 30,000-50,000 hours and handle 60G acceleration. They would be quite suitable. I don't think they'd actually be needed.

4 The Lambda Probe Oxygen Sensor is attributed to Robert Bosch GmbH during the late 1960s under the supervision of Dr. Günter Bauman. Im not sure if there was an equal sensor possible at the time, but I think there probably was. It would be useful for the kind of 2 stroke engines people were working on and indeed I see no problem incorporating it with the controls of the day. I'm just not sure if there was such a device in existence.

Personally I think had it not been for the jet engines 2 stroked turbo supercharged disels were the future. They stood a chance of actually producing 4000hp on 12-16 cylinder instead of 24,28 or 36.

In what way?

Other than being instantly programmable (i.e. being altered in 5seconds instead of needing a new cam ground) it does exactly the same thing.

It allows ignition timing, boost and fuel to be altered on the basis of inputs of temperture, pressure, and load. Most WW2 engines were NOT limited in performance

by virtue of over simplified control systems. They were limited by all the fundamental physics that wasnt yet sorted out, mostly combustion system

understanding.

All the tiny tweaking of transient performance is meaningless in a virtually constant speed engine like aero-engines.

The engines in the lab in 1940 were instrumented to similar degrees as they are now, cylinder pressure, EGT, exhaust gas analysis, albeit very laboriously and without nice logging, but the kommandogerats (etc) were not fred flintstone items and although of course you`d chuck them in the bin now, throwing them away will only gain you convenience not performance.

The lambda sensor was possible in 1930s. It is just a Nernst Cell, invented in 1899 by Walther Nernst. It is attributed to Robert Bosch in 1960 but they just industrialised it. The Lambda sensor was introduced mainly to control Catalytic converters but its ability to improve performance was soon appreciated. The cell would give an electrical output proportional to oxygen, using 1930s technology this could ve be displayed in a dial gauge but also amplified and used to drive a small servo motor, say 2.5W which could adjust the mixture In the carburettor/fuel system.

Last edited:

Admiral Beez

Major

I loved my 2000 Saturn SL2. It was this second generation that I preferred. Too bad it rusted out beneath the plastic panels.The original Saturn S-series was competitive when it first came out. When Honda redesigned the Civic for 1993 model year, the Saturn was a generation behind.

I loved my 2000 Saturn SL2. It was this second generation that I preferred. Too bad it rusted out beneath the plastic panels.

Whatever happened with using plastic panels? Not terribly popular.

Admiral Beez

Major

I liked them. I was side swiped on a highway off ramp. Their car spun and wrecked itself in a ditch. My Saturn had a shattered side panel. I drove to the junkyard and with a few wingnuts swapped out the panel.Whatever happened with using plastic panels? Not terribly popular.

I liked them. I was side swiped on a highway off ramp. Their car spun and wrecked itself in a ditch. My Saturn had a shattered side panel. I drove to the junkyard and with a few wingnuts swapped out the panel.

Are you referring to hardware or your friends?

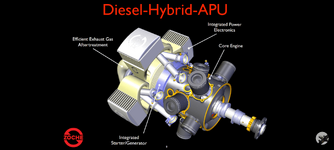

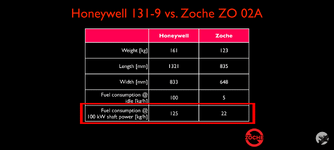

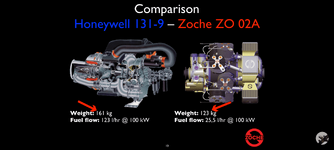

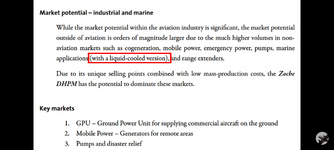

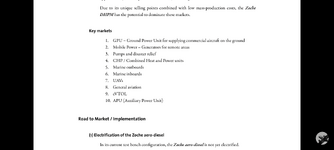

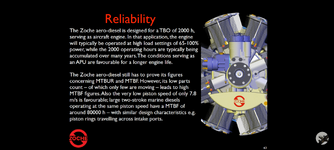

Let's Go Aviate has a very long overdue update on Zoche Engine progress which looks very promising. More efficient, more power, much bigger market potential = reduced costs... Boeing and Airbus interested to use as a much better APU replacement for the Honeywell 131-9.

View: https://youtu.be/wAb_vxdYLUI

View: https://youtu.be/wAb_vxdYLUI

Attachments

-

Certification and Industrialisation.png325.6 KB · Views: 4

Certification and Industrialisation.png325.6 KB · Views: 4 -

Diesel Hybrid Power Module (DHPM).png314.1 KB · Views: 4

Diesel Hybrid Power Module (DHPM).png314.1 KB · Views: 4 -

Honeywell 131-9 vs Zoche ZO 02A - BSFC kg Dimensions.png43 KB · Views: 7

Honeywell 131-9 vs Zoche ZO 02A - BSFC kg Dimensions.png43 KB · Views: 7 -

Honeywell 131-9 vs Zoche ZO 02A - kg fuel flow comaprison.png269.6 KB · Views: 4

Honeywell 131-9 vs Zoche ZO 02A - kg fuel flow comaprison.png269.6 KB · Views: 4 -

Honeywell 131-9 vs Zoche ZO 02A - Size Comparison.png142.2 KB · Views: 3

Honeywell 131-9 vs Zoche ZO 02A - Size Comparison.png142.2 KB · Views: 3 -

Letter Screenshot_20251130-110241.png79.1 KB · Views: 4

Letter Screenshot_20251130-110241.png79.1 KB · Views: 4 -

Market potential - industrial and marine - Key markets 1.png374 KB · Views: 6

Market potential - industrial and marine - Key markets 1.png374 KB · Views: 6 -

Market potential - industrial and marine - Key markets 2.png50.2 KB · Views: 6

Market potential - industrial and marine - Key markets 2.png50.2 KB · Views: 6 -

Reliability.png507.6 KB · Views: 4

Reliability.png507.6 KB · Views: 4 -

Specific Power vs Take-Off Power kW Comparison 2.png70.9 KB · Views: 5

Specific Power vs Take-Off Power kW Comparison 2.png70.9 KB · Views: 5 -

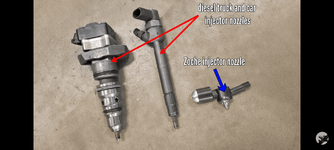

Zoche Injector.png937.2 KB · Views: 4

Zoche Injector.png937.2 KB · Views: 4

GregP

Major

In the Amsoil Engine Masters Challenge, did the engines have to produce power for 8 - 10 hours at a time at 75% or so power or just run long enough to get dyno tested? That was a worst-case London-to-Berlin and back mission (last to take off, last to land). The engines of the day were good for many such missions. Many are still flying today, albeit at lower usage rates than watime.If you look at the outputs of the Amsoil Engine Masters Challenge I think you would be surprised. In 2019 they got 800hp out of a 440CI LS-4 engine.

I think engine reliability would go up tremendously, along with power, and improvements in valves, valve train, blowers, turbos, waste gates, internal friction that fuel efficiency would also improve.

Cheers,

Biff

Just curious.

They can make a AA Fuel drag engine produce 13,000 hp from less than 800 cubic inches, but it doesn't last for more than maybe 5 seconds at full power. Amazing, but hardly useful for an aircraft needing to fly 8 - 10 hours at time.

Cheers, BiffF15!

Last edited:

The Zoche diesel looks good on paper, and the latest iteration with an electrical hybrid turbocharger is an interesting enhancement, notably Porsche has done essentially the same in the latest 911. And targeting other markets outside GA makes sense, considering how small and moribund GA is.

However, Zoche has been promising this or that since the 1980'ies but has yet to deliver anything to the market. Not holding my breath.

However, Zoche has been promising this or that since the 1980'ies but has yet to deliver anything to the market. Not holding my breath.

GregP

Major

When I said not even close, I was referring to the size and horsepower. NOBODY is making a 2,000 hp radial or inline for general aviation use since there isn't a requirement for it and no government is paying for the fuel if there were such a beast. We basically make piston engines from about 100 up to about 350 hp, suitable for 1 - 6 passenger civil light aircraft.The Lycoming IO-360 makes 200hp in certified form, which gives 0.55 hp/ci (up to 220hp for experimental: 0.65 hp/ci). Gives some idea of what modern aircraft engines are giving out.

If they need more power, they go to turbines.

The Rotec radial is out there but has a terrible reputation for lack of longevity. It seems to grenade after very little use. The Lycoming O-720 is likely still available, but hardly anyone uses it due to acquisition cost, overhaul cost, and fuel burn, not to mention trying to start it when hot. I have seena twin turbo version run, but it doesn't run often or for too long.

Shortround6

Lieutenant General

The Lycoming IO-360 makes 200hp in certified form, which gives 0.55 hp/ci (up to 220hp for experimental: 0.65 hp/ci). Gives some idea of what modern aircraft engines are giving out.

We don't really know what a "modern" reciprocating engine can really do because we stopped developing them in the 1960s.

I have very little idea of what the overhaul life was in the 1950s and 1960s but the post 60s was a shift to longer engine life and using cheaper fuel.

In the 60s Lycoming and Continental were making some relativity high powered engines. But they were complicated and needed 100/130 fuel. 340hp from a 480cu in engine was not easy even at 3400rpm. The Lycoming IGSO-480-A1A6 engine needed fuel Injection (port injection), Reduction Gears, a gear driven Supercharger that could provide 9lbs of boost all they way up to 11,000ft.

Turbos replaced the gear driven superchargers at the end of 60s but engine life and overhaul costs were not looking good even in the 350-400hp range. P&W Canada was offering the early PT-6A engines at around 465hp at less than 1/2 the weight.

Most owners of 4-6 passenger single engine planes did not want the cost of maintaining the complicated engines or buying 100/130 fuel.

Switching to 540cu in engines without superchargers or reduction gears gave much reduced operating expenses for the single engine airplanes, and the big "rush" to pressurized 4-6 aircraft didn't happen (there were some but not a lot) so the lack of superchargers was not that big a deal. Made airframe annual maintenance a lot cheaper.

By the 1980s/90s they were getting hundreds more hours out of the basic old designs between overhauls. The manufactures were concentrating on engine life and low overhaul costs instead of gee-whiz performance. The General aviation crash and liability insurance problems also had a lot to do with lack of development in the last 30-40 years.

We now need not only a "new" engine, we need one that will run on fuel that is still being made 7-10 years from now and the engine has to be not only bullet proof, it has to be very large caliber bullet and lawyer proof when a number of years old without extraordinary maintenance procedures.

comparing to car engines is not easy. Most cars only use 20-30hp when cruising on the high way despite what they can make at full throttle. A 4 seat airplane needs over 40% power just to stay in the air and more like 50-65% power at cruise. Try using 3rd gear in you car on the highway for several hundred hours and see how long the engine lasts

We don't really know what a "modern" reciprocating engine can really do because we stopped developing them in the 1960s.

I have very little idea of what the overhaul life was in the 1950s and 1960s but the post 60s was a shift to longer engine life and using cheaper fuel.

In the 60s Lycoming and Continental were making some relativity high powered engines. But they were complicated and needed 100/130 fuel. 340hp from a 480cu in engine was not easy even at 3400rpm. The Lycoming IGSO-480-A1A6 engine needed fuel Injection (port injection), Reduction Gears, a gear driven Supercharger that could provide 9lbs of boost all they way up to 11,000ft.

Turbos replaced the gear driven superchargers at the end of 60s but engine life and overhaul costs were not looking good even in the 350-400hp range. P&W Canada was offering the early PT-6A engines at around 465hp at less than 1/2 the weight.

Most owners of 4-6 passenger single engine planes did not want the cost of maintaining the complicated engines or buying 100/130 fuel.

Switching to 540cu in engines without superchargers or reduction gears gave much reduced operating expenses for the single engine airplanes, and the big "rush" to pressurized 4-6 aircraft didn't happen (there were some but not a lot) so the lack of superchargers was not that big a deal. Made airframe annual maintenance a lot cheaper.

By the 1980s/90s they were getting hundreds more hours out of the basic old designs between overhauls. The manufactures were concentrating on engine life and low overhaul costs instead of gee-whiz performance. The General aviation crash and liability insurance problems also had a lot to do with lack of development in the last 30-40 years.

We now need not only a "new" engine, we need one that will run on fuel that is still being made 7-10 years from now and the engine has to be not only bullet proof, it has to be very large caliber bullet and lawyer proof when a number of years old without extraordinary maintenance procedures.

comparing to car engines is not easy. Most cars only use 20-30hp when cruising on the high way despite what they can make at full throttle. A 4 seat airplane needs over 40% power just to stay in the air and more like 50-65% power at cruise. Try using 3rd gear in you car on the highway for several hundred hours and see how long the engine lasts

Interesting "entry" into the GA market.

www.deltahawk.com

www.deltahawk.com

Small Aircraft Jet Fueled Engine - DeltaHawk Engines

Powerful Technology Through Time-Proven Innovation. The first clean sheet piston engine design FAA certified in over 60 years.

www.deltahawk.com

www.deltahawk.com

The Lycoming IO-360 makes 200hp in certified form, which gives 0.55 hp/ci (up to 220hp for experimental: 0.65 hp/ci). Gives some idea of what modern aircraft engines are giving out.

We don't really know what a "modern" reciprocating engine can really do because we stopped developing them in the 1960s.

So far the only really successful new entrant into the GA market is the Rotax 900 series. They only play in the smaller end of the market though, 80-160 hp. 5800 rpm max, 2000 h TBO, and the higher end models have turbocharging, (port ?) fuel injection, and FADEC. And runs on standard RON 95 automotive gas as well as 100LL.

comparing to car engines is not easy. Most cars only use 20-30hp when cruising on the high way despite what they can make at full throttle. A 4 seat airplane needs over 40% power just to stay in the air and more like 50-65% power at cruise. Try using 3rd gear in you car on the highway for several hundred hours and see how long the engine lasts

An automotive engine conversion that has seen some success is the ex-Thielert and Austro diesel engines based on the Mercedes OM640. But that's a van engine, and a diesel, so presumably somewhat sturdily built for long life from the get go. And the aviation models are AFAIK somewhat downrated compared to the automotive original.