SaparotRob

Unter Gemeine Geschwader Murmeltier XIII

It works this time!

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Ad: This forum contains affiliate links to products on Amazon and eBay. More information in Terms and rules

It's true, I read it on the internet!Every allied aircraft was derived from a Fokker or a Focke or some other miss spelling.

If anything, the F8F's design was influenced by US Navy veteran pilot's input.

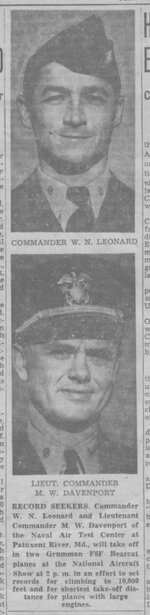

"It's difficult to determine from the file, but the U.S. national record in 1946 was either 'Fastest Climb to 10,000 Feet,' or 'Time to Climb 3,000 Meters.' The switch from feet to meters occurred around that time, presumably to gain acceptance from the international community at FAI.

"In any event, both performances were calculated and the time to 10,000 feet was 97.8 seconds; the time to 3,000 meters (9,843 feet) was 96.1 seconds.

"The record I quoted was set by LCDR M.W. Davenport in a Bearcat on November 22, 1946, in Cleveland."

editedThe Spitfire 9 came about because of the Fw 190. Was the F-15 a copy of the MiG-25? Technologies advances and so does the competition. Look at modern motor sports. It's an arms race in which having yesterday's tech loses.

Excellent insight Rich, as always.Properly prepared, on a good day, with good pilots, the F8F climb to time could indeed be remarkable.

November 22, 1946 . . . Cleveland Air Show . . . Operation Pogostick . . . two F8F-1 from TacTest at the NAS Patuxent NATC are prepared for climbs to 10000 feet. Both aircraft have the WEP safety interlock bypassed allowing WEP with wheels down, something standard configuration does not allow. Both aircraft are otherwise standard, armed, but no ammo, with about 50% fuel. Each is equipped with what was called a "theater" installed behind the pilot's seat. This was a small instrument board, about one-foot square, that had as it's most important feature a movie camera that recorded time, altitude, and various goings on in the cockpit. The camera was actuated thusly: the pilot taxied the airplane to his starting point and flipped a switch to activate the camera. At that point, when the pilot releases his brakes, another switch is automatically thrown and the camera starts recording events.

In this particular instance, the cameras were calibrated by National Aeronautics Association for the climb attempts. By reviewing the film it became relatively academic to determine the time take to reach 10000 feet or 3000 meters, which ever you wanted to look at.

First to go was CDR Bill Leonard, Projects Director at TacTest, from a dead stop to 10K feet in 100.0 seconds, including a 150 foot take off run. LCDR Butch Davenport, F8F Projects Officer at TacTest, came along about 30 minutes later and set the next new record of 97.8 seconds, including a 115 foot take off run. Leonard's take off was into an estimated 30 knot head wind, by the time Davenport took off the head wind was over 40 knots. This higher wind speed helped to reduce Davenport's time on the ground. I have never seen Davenport's pilot's log book, but I have Leonard's in my possession. It shows his run and earlier practice runs made at TacTest in preparation.

Being once challenged in my reporting of this event I once took, in December 2003, the extra step of contacting the NAA, the result being this from Art Greenfield, then, Director, Contest and Records, National Aeronautic Association:

It is too bad that the international climb-to-time record category was not established until 1950; after first being proposed for inclusion by the US's National Aeronautic Association at the June 1950 Fédération Aéronautique Internationale General Conference. According to Thierry Montigneaux, of the FAI, "The first mention of a 'time to climb' world record in our books was for a flight made by a British pilot onboard a Gloster Meteor on 31 August 1951. No performance set in 1946 could therefore have qualified as an official 'world' record, as this category of record did not exist then." The pilot of the Meteor was Flt Lt Richard B Prickett; his time to 3000 meters was 75.5 seconds.

So, in 1946 there was no "World Record" class for climb to time.

The rapid climb to altitude was the F8F's bread and butter. The plane was to have been one of the solutions to the kamikaze problem ... rapid climbs capability, firepower, speed, and more (better) maneuverability than the F6F or F4U.

View attachment 742690View attachment 742691

Both airframes sported NACA 230xx airfoils but the F8F was 'fatter'.I have heard of it before.

How true it is something else.

The company history is unlikely to credit a foreign design as being the basis (or even inspiration) for one of their major aircraft, so that may not be a good avenue to pursue. Official line is that Roy Grumman was becoming worried that the twin engine designs they were working on (like the F7F) were too big for the majority of the navies carriers and would have a limited market. End of July 1943 he sent an outline to his chief engineer, Bill Schwendler, proposing a new lighter fighter.

I don't know when in 1943 Robert Hall is supposed to have flown the 190.

Aside from a few features in the the engine installation I am not sure what the Fw 190 and F8F have in common.

I would note that such features as the sliding bubble canopy were becoming quite common in US fighter designs at this time (even if taking a while to show up in production) so it takes more than few superficial items to really back up this story.

Hi Barrett.I was present when Bob Hall related his experience with the FW 190 ref. the F8F. He spoke at a meeting of the American Fighter Aces Assn.

This is the way I've always understood the reason for the F8F to exist.The F8F looks like Mr Grumman asked his designers to build the smallest airframe around the biggest engine with heritage from the F6F.

I suggest you look up 1940 race cars. You will find that for racing the always meted the most powerfull en light engine a a frame as light they deared to makeIt's like some people say, "what was the auto industry thinking?

Good call on the F8F.This is the way I've always understood the reason for the F8F to exist.

It was, basically, the F6F put on a diet, creating, as Joe stated so eliquently...The smallest airframe around the largest engine.

You could say the same for the FM-2, which was based on the experimental F4F-8. Again, reengineered to create a smaller, lighter airframe around a larger, more powerful engine.

...and climb benefitted there, as well (2300 vs. 3650).

The biggest visual difference between a Bearcat and a Sea Fury is the paint job. Underneath the paint job they have nothing in common.It's an example of convergent evolution. Same principle that led to the similarity between the F8F and the N1K2.

I think the niggest difference is size. The Bearcat is small; the Sea Fury is large.The biggest visual difference between a Bearcat and a Sea Fury is the paint job. Underneath the paint job they have nothing in common.