Deleted member 68059

Staff Sergeant

- 1,056

- Dec 28, 2015

Then you consistently deny that Germany was suffering from an oil shortage from the very beginning.

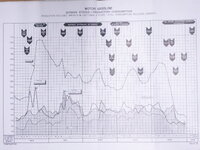

Data says no.

Stocks of vehicle gasoline didn't fall seriously until mid 1944. (German tanks were Petrol fuelled, with your reference to the Polish ground campaign),

until then production more or less equalled consumption.