wiking85

Staff Sergeant

Ural bomber - Wikipedia

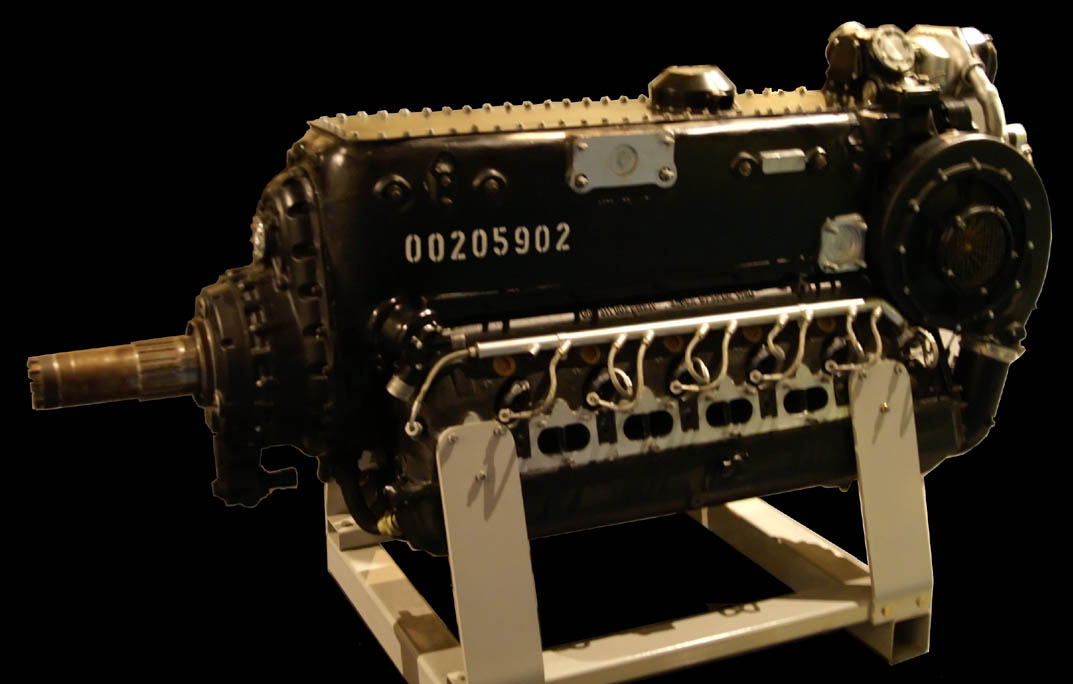

The historical designs were obviously not up to the mark, but could they have been? The Do 19 was clearly too flawed at the basic level, but the Ju89 was developed further eventually into the 290 and 390 versions after converting into a civilian airliner, the Ju90. An interesting discovery I recently made was about the Ju86, which was originally equipped with the Jumo 205 diesel aviation engine, which was found to not be able to handle the rapid throttle changes that came with combat in a medium bomber flying at lower altitudes in 1936 in Spain. It was initially selected because it was considerably more fuel efficient than the standard gasoline engines, up to 35% more efficient. This actually matches the fuel consumption differential between the Jumo 205 and the B17's engines, as the Jumo diesel consumed 1/3rd less fuel than the radial air-cooled B17 engines running on gasoline. The Jumo 205 was developed in a number of ways and ended up generating as much power or more in different configurations/designations. The equivalent Jumo 207 with turbosupercharger produced the same power as the American radial engines with much less refined fuel, though with slightly greater weight. Though diesels are much more fuel efficient they are heavier and lower power per KG. Still given higher altitudes and the lack of need for significant engine throttle changes diesel aero-engines are actually really good for long range purposes.

Then I remembered the application of 6 Jumo 207's historically:

Blohm & Voss BV 222 Wiking - Wikipedia

So what if the Junkers company disregarded the restrictions of the RLM and the RLM was more forward thinking and accepted what Junkers offer with a 6x Jumo 205 diesel fueled Ju89? The wing area could be cut down on with more power and given the Ju390 later on a 6x engine long range bomber was not a problem. We could even reference the B36, but a pusher configuration is beyond the scope of this what if. But with 6 such engines and 1/3rd lower fuel consumption per engine, the Ural bomber concept was viable for much greater than the specifications called for. The Urals could actually be reached and hit from East Prussia by 1941 with a developed Ju89 with Jumo 207 engines.

Junkers Jumo 5 / Jumo 205

Given that heavy bombers are going to operate at higher altitudes and Soviet aircraft engines had serious problems with altitude due to lack of production turbo or higher altitude superchargers even in 1944, diesel aero-engines and more of them might have been the answer.On the long transatlantic routes, the Jumo 205 Diesel engine was a very economic engine due to the low fuel consumption. On the other hand these long range routes with hours of cruise power were an optimum for the Diesel engines.

Junkers Jumo 207

That's also assuming the Jumo 208 is not started earlier to provide greater power for a 4 engine bomber: Junkers Jumo 208

Nearly 1500hp for takeoff, 1000hp at continuous use. Better than the B17 at 1/3rd less fuel cost.

Best yet, diesel fuel was abundant in Germany relative to any other type of fuel, since really on the navy used diesel engines. Avgas would be a major constraining factor for heavy bomber use, but diesel wouldn't be a problem.

Also before anyone complains about production costs, over 1,200 He177 heavy bombers were built during WW2 as well as several other 4 engine types like the Fw200 among others.

If there is a working long range bomber available for maritime aviation use too and uses naval fuel for use, then it has multiple roles beyond just bombing Russia. For higher altitude work the Germans could operate over Britain until September 1942, which was the first time a British fighter was able to intercept a high altitude Ju86P using the Jumo 207 engine.

What are the thoughts of the community?