I didn't mean exact copies or duplicates. Though I'm not sure I agree with your conclusions. Hellcat or Corsair would have been helpful to have on the Russian Front and in the MTO. And I doubt P-47 was harder to maintain even with the turbo.

LW already have had as much Fw 190s as the industry was able to manufacture. For each 3 Corsairs or Hellcats there is 4 Fw 190 that don't get produced?

Someone will need to 1st produce turbo set-up for the German copy of P-47 1st - not a given, considering German (bad) luck with turboes. And then to make sure it works on thousands of aircraft in service, plus patching out the battle damage.

Fuel is definitely a problem regardless what planes the Luftwaffe were flying. But maybe with more and better aircraft in the Mediterranean they might have eventually been able to source some Middle Eastern oil. I don't see any advantage to building aircraft, particularly bombers, that are just going to be shot down.

Germany can't just handwave both better and more aircraft. Especially the high-performance 2-engined aircraft, that also push fuel requirements through the roof.

Without invasion of Soviet Union, Germany stands some chances in seecuring ME oil. Or, force the UK into some workable peace by 1940/41. Historically, peace/armistice vs. UK never happened, invasion happened, so they will never get the oil from ME.

I wouldn't say automatically better, but it seemed to be better in aggregate. Both Bf 109 and MC 202 were performing better at above 20' feet than Spitfire Mk V or merlin P-40, and much better than any Allison engined P-40 or P-39... or any Klimov or Shvestov-engined fighter. With the two speed superchargers they had to always pick the two altitudes where performance was optimal (and they didn't always guess right with this), but the hydromatic seemed to perform well at all altitudes up to it's performance ceiling.

What Bf 109 out-performed than the Spitfire V or Merlinized P-40? MC.202 was not out-pacing the Spitfire V or P-40F above 20k ft, even if it should out-climb the heavy P-40F.

MC.202 and Bf 109F shed a lot of drag due to being small aircraft - see for example Re.2001 and Ki-61 not being that speedy despite the variable-speed S/C on their engines.

P-40N and P-39N/Q were faster than MC.202. P-40B was as fast as the Bf 10E, despite the former being bigger and heavier.

MiG-3 was out-pacing Bf 109F2, despite having the 1-speed S/C on the AM-35A vs. the variable-speed S/C on the German machine. Yak-1 was faster than the Bf109E, despite the engine power being a bit better on the 109E.

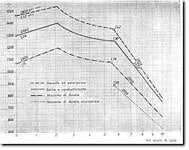

Above rated altitude, there is no appeal of the variable-speed S/C. With 100 oct fuel, Allied engines all but negated the supposed disadvantage of the 2-speed drive anyway. See here the power chart of the Merlin 20 series.

Pray tell, how should the piston-engined mid-war (1942-43) German fighter should've looked?I never said it was. But what they needed was more successful designs in the mid war. Like the aircraft I mentioned. Instead they extended the life of pre-war or early war designs past their freshness date. One of the disadvantages of keeping the same design's in action through the war was that the enemy learned the entire performance envelope, quirks and flaws of the design. Certain problems with the 109 for example were well known by late 1942 and were exploited by Allied pilots. With a variety of newer designs arriving it's much harder to develop ideal tactics.

It's a lot of incremental changes but it's arguable how new they were. Certainly in terms of capability they were very new.

Another question: in order to successfully battle the Allied best past late 1943, what engine should be powering a brave new German fighter - piston engine or jet engine? Not just to equal 430-440 mph turn of speed, but to out-speed them at least 20 mph, and to out-climb them, and to have manageable handling.

I certainly never suggested that. I was pointing out rather that they were failing to produce promising new designs (and it's also true that they failed to develop some good new ones in time).

Me 262 was a promising new design. A lot of people will argue that He 280 was a promising new design. Neither of the two will not be produced in quantities unless/until there are thousands of jet engines available for installation.

So I would say, technically it was possible to make a faster tactical bomber, a real replacement for the pre-war Stuka or the early war Ju 88, but they never really did. The Arado 234 seems to have been quite a promising design but they couldn't get it into large scale production I gather mainly due to engines.

Thanks for the feedback, there are many sentences there that I agree, and some that I will not agree (guess this is why forums exist)

However, the question of what types specifically were supposed to be hard to produce still remains.