syscom3

Pacific Historian

This is quite interesting. I didnt know this project existed till this morning.

Top Secret Project Ivory Soap -- Aircraft Repair Ships

Top Secret Project Ivory Soap -- Aircraft Repair Ships

by Bruce Felknor

As 1943 ended, German forces had been defeated in Africa, and Italian troops were helping the Allies drive Germany out of their country. Operation Overlord and the Normandy landings were far advanced in strategic planning. Major planning efforts were under way to hasten victory in the Pacific.

The top-secret atomic bomb was a year and a half from its first test. In the Pacific Theater everything depended on conventional warfare, with B-29s bombers carrying the island-hopping war all the way to the Japanese home islands, with P-51s protecting the bombers.

One thing was certain: the invading aircraft would face a skilled and deadly foe in the air. Major damage to our planes was inevitable, but many of them would limp safely back to base. What then? No advanced air field had either the men or the machine shops and other facilities necessary for major airplane and engine repair and rebuilding.

Thus was born Ivory Soap, a secret project kept "classified" for more than a half-century. It is not even mentioned in the official history book "The Army Air Forces In World War II."

The idea arose in Air Corps staff meetings in Tunisia and Italy. It then went to Washington, where it was approved by the commander of the Army Air Corps, Gen. Henry H. "Hap" Arnold, and by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Ivory Soap consisted of 24 ships and some 5,000 men drawn from the Army, Navy, and Merchant Marine. The ships were six Libertys and eighteen 180-foot freight/salvage (F/S) auxiliary vessels that were converted into floating machine shops and repair and maintenance depots. Their main "clients" would be B- 29s and P-51s but they could handle any other aircraft as necessary.

The Libertys were designated Aircraft Repair Units, Floating (ARUs), each with a total complement of 344 men. The Aircraft Maintenance Units (AMUs) were 187 foot long ships built by Higgins in New Orleans and had a complement of 48 men. The ARUs (Libertys) had shop space big enough to accommodate components of the enormous B-29s. The more numerous and smaller AMUs could handle the fighters. Because of their shorter cruising range fighters advanced bases had to be more numerous, and closer to the targets; so did their floating repair depots.

The ships were operated by the Army Transport Service (ATS), all of whose officers and men were merchant mariners. They were well-armed against air attack: each Liberty had a 3-inch 50 at the bow and a 5-inch 38 aft, plus twelve 20mms and two 40mms. Proportionately less firepower went aboard the auxiliaries. The guns were manned by Naval Armed Guard crews.

Acquiring the ships and getting them to the deepwater terminal at Point Clear, close to the Marine Air Technical Services Command at Brookley Field, outside Mobile, Alabama, began in the spring of 1944. Once in place, they had to be modified. For the Libertys this meant fitting them with machine tools, cranes, and all the elements of complete machine shops. Similarly, equipment for sheet metal work, fabric repair facilities. They carried a large inventory of steel, lumber, aluminum, and other materials to manufacture needed parts.

Facilities had to be built into the ships to accommodate two big R-4B Sikorsky helicopters on board. These were to locate downed planes, rescue their flight crews and passengers, ferry shipwrights and mechanics wherever they might be needed on the islands of the Pacific campaign, and to haul parts.

Each ship was also equipped with two motor launches and two DUKWs or "ducks," amphibious trucks for carrying parts too heavy for the helicopters. Divers were part of each crew, so room for their support equipment was also necessary.

Similar work on the 18 smaller maintenance vessels, which would be principally concerned with smaller fighter planes, went on simultaneously. When the ships were ready, so were their crews and repair teams. Selecting the men and training them for the unfamiliar parts of their new assignments took time. The mechanics and machinists had to learn rudiments of seamanship and swimming, including how to abandon ship if need be. The Assistant Commandant was C. E. Hooten, a Mariner, and other Merchant Marine Officers were part of the Army teaching staff at Point Clear

All Army technicians required marine survival skills before they could board the 24 depot repair ships at Mobile, Alabama in 1944

The Liberty ships selected for Ivory Soap were:

Original name Name as Aircraft Repair ship

Rebecca Lukens Maj. Gen. Herbert A. Dargue

Nathaniel Scudder Brig. Gen. Alfred J. Lyon

Richard O'Brien Brig. Gen. Asa N. Duncan

Robert W. Bingham Brig. Gen. Clinton W. Russell

Daniel E. Garrett Maj. Gen Robert Olds

Thomas LeValley Maj. Gen. Walter R. Weaver

Inevitably, the six hybridized Libertys were known as "The Generals." The 18 auxiliaries, each named in honor of an Army Colonel, naturally, were "The Colonels."

These ships returned hundreds of wrecked or seriously damaged B-29s and fighters to battle.

On October 1, 1944, SS Maj. Gen. Herbert A. Dargue sailed for New Orleans, then to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to join a convoy through the Panama Canal. Once in the Pacific, she sailed alone, chugging along at the Libertys 10 knots per hour toward Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands. There the Dargue was ordered to Saipan, in the Marianas, where heavy action was about to begin. In November they dropped the hook in Tanapag Harbor near Saipan.

One of the ship's helicopter pilots, First Lt. Daniel A. Nigro, recently recalled some of their experiences in an interview with Sue Baker for the Air Corps magazine Airman at Wright- Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. (See her story online at Water Wings )

Nigro and his fellow pilot, John Halpin, flew repair personnel to airstrips on the island and returned with aircraft parts needing repair in the Dargue's shops. Frequently they would carry so many parts needing repair that they taxed the helicopter's capacity. "We did anything -- even taking off the 'copter doors--to lighten our load," he said.

While the Dargue was at Saipan her gun crew shot down two Japanese "Betty" bombers. They got another Japanese plane in May after they moved on to Iwo Jima.

The information in this article came to me through Fred M. Duncan, who was a 16-year-old merchant seaman when he found himself part of Project Ivory Soap. Now the survivors of that hardy band are in the seventies to nineties.

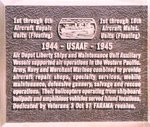

Small honors have been paid to them at last. The Air Force Museum at Dayton, Ohio, established a museum exhibit commemorating the ships and men of Ivory Soap.

A Memorial Plaque was dedicated there on October 3, 1997. Fred Duncan and other survivors from all three services--Army, Air Corps, Naval Armed Guards, and Merchant Marine assembled in a reunion at Washington, D.C., in October 1998.

Dear reader, if you or anyone you know was part of the historic but invisible operation, please send word to Fred or to me. We merchant marine veterans, at least, can comprehend the risks and perils faced by the Ivory Soap boys, and offer our own sophisticated tribute to these brave shipmates, who helped win the war in the Pacific.

Sources:

The Liberty Ships; The history of the"emergency" type cargo ships constructed in the United States during World War II, L. A. Sawyer and W. H. Mitchell, Cambridge, Maryland: Cornell Maritime Press, 1970

A History of the Army Aircraft Repair Ship Project, Nov. 1943-Sept. 1944, U.S. Army Air Forces, Feb. 14, 1945

Photo of Merchant Marine Officer teaching lifeboat skills to the Army crewmembers courtesy of Fred Duncan

Top Secret Project Ivory Soap -- Aircraft Repair Ships

Top Secret Project Ivory Soap -- Aircraft Repair Ships

by Bruce Felknor

As 1943 ended, German forces had been defeated in Africa, and Italian troops were helping the Allies drive Germany out of their country. Operation Overlord and the Normandy landings were far advanced in strategic planning. Major planning efforts were under way to hasten victory in the Pacific.

The top-secret atomic bomb was a year and a half from its first test. In the Pacific Theater everything depended on conventional warfare, with B-29s bombers carrying the island-hopping war all the way to the Japanese home islands, with P-51s protecting the bombers.

One thing was certain: the invading aircraft would face a skilled and deadly foe in the air. Major damage to our planes was inevitable, but many of them would limp safely back to base. What then? No advanced air field had either the men or the machine shops and other facilities necessary for major airplane and engine repair and rebuilding.

Thus was born Ivory Soap, a secret project kept "classified" for more than a half-century. It is not even mentioned in the official history book "The Army Air Forces In World War II."

The idea arose in Air Corps staff meetings in Tunisia and Italy. It then went to Washington, where it was approved by the commander of the Army Air Corps, Gen. Henry H. "Hap" Arnold, and by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Ivory Soap consisted of 24 ships and some 5,000 men drawn from the Army, Navy, and Merchant Marine. The ships were six Libertys and eighteen 180-foot freight/salvage (F/S) auxiliary vessels that were converted into floating machine shops and repair and maintenance depots. Their main "clients" would be B- 29s and P-51s but they could handle any other aircraft as necessary.

The Libertys were designated Aircraft Repair Units, Floating (ARUs), each with a total complement of 344 men. The Aircraft Maintenance Units (AMUs) were 187 foot long ships built by Higgins in New Orleans and had a complement of 48 men. The ARUs (Libertys) had shop space big enough to accommodate components of the enormous B-29s. The more numerous and smaller AMUs could handle the fighters. Because of their shorter cruising range fighters advanced bases had to be more numerous, and closer to the targets; so did their floating repair depots.

The ships were operated by the Army Transport Service (ATS), all of whose officers and men were merchant mariners. They were well-armed against air attack: each Liberty had a 3-inch 50 at the bow and a 5-inch 38 aft, plus twelve 20mms and two 40mms. Proportionately less firepower went aboard the auxiliaries. The guns were manned by Naval Armed Guard crews.

Acquiring the ships and getting them to the deepwater terminal at Point Clear, close to the Marine Air Technical Services Command at Brookley Field, outside Mobile, Alabama, began in the spring of 1944. Once in place, they had to be modified. For the Libertys this meant fitting them with machine tools, cranes, and all the elements of complete machine shops. Similarly, equipment for sheet metal work, fabric repair facilities. They carried a large inventory of steel, lumber, aluminum, and other materials to manufacture needed parts.

Facilities had to be built into the ships to accommodate two big R-4B Sikorsky helicopters on board. These were to locate downed planes, rescue their flight crews and passengers, ferry shipwrights and mechanics wherever they might be needed on the islands of the Pacific campaign, and to haul parts.

Each ship was also equipped with two motor launches and two DUKWs or "ducks," amphibious trucks for carrying parts too heavy for the helicopters. Divers were part of each crew, so room for their support equipment was also necessary.

Similar work on the 18 smaller maintenance vessels, which would be principally concerned with smaller fighter planes, went on simultaneously. When the ships were ready, so were their crews and repair teams. Selecting the men and training them for the unfamiliar parts of their new assignments took time. The mechanics and machinists had to learn rudiments of seamanship and swimming, including how to abandon ship if need be. The Assistant Commandant was C. E. Hooten, a Mariner, and other Merchant Marine Officers were part of the Army teaching staff at Point Clear

All Army technicians required marine survival skills before they could board the 24 depot repair ships at Mobile, Alabama in 1944

The Liberty ships selected for Ivory Soap were:

Original name Name as Aircraft Repair ship

Rebecca Lukens Maj. Gen. Herbert A. Dargue

Nathaniel Scudder Brig. Gen. Alfred J. Lyon

Richard O'Brien Brig. Gen. Asa N. Duncan

Robert W. Bingham Brig. Gen. Clinton W. Russell

Daniel E. Garrett Maj. Gen Robert Olds

Thomas LeValley Maj. Gen. Walter R. Weaver

Inevitably, the six hybridized Libertys were known as "The Generals." The 18 auxiliaries, each named in honor of an Army Colonel, naturally, were "The Colonels."

These ships returned hundreds of wrecked or seriously damaged B-29s and fighters to battle.

On October 1, 1944, SS Maj. Gen. Herbert A. Dargue sailed for New Orleans, then to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to join a convoy through the Panama Canal. Once in the Pacific, she sailed alone, chugging along at the Libertys 10 knots per hour toward Eniwetok in the Marshall Islands. There the Dargue was ordered to Saipan, in the Marianas, where heavy action was about to begin. In November they dropped the hook in Tanapag Harbor near Saipan.

One of the ship's helicopter pilots, First Lt. Daniel A. Nigro, recently recalled some of their experiences in an interview with Sue Baker for the Air Corps magazine Airman at Wright- Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. (See her story online at Water Wings )

Nigro and his fellow pilot, John Halpin, flew repair personnel to airstrips on the island and returned with aircraft parts needing repair in the Dargue's shops. Frequently they would carry so many parts needing repair that they taxed the helicopter's capacity. "We did anything -- even taking off the 'copter doors--to lighten our load," he said.

While the Dargue was at Saipan her gun crew shot down two Japanese "Betty" bombers. They got another Japanese plane in May after they moved on to Iwo Jima.

The information in this article came to me through Fred M. Duncan, who was a 16-year-old merchant seaman when he found himself part of Project Ivory Soap. Now the survivors of that hardy band are in the seventies to nineties.

Small honors have been paid to them at last. The Air Force Museum at Dayton, Ohio, established a museum exhibit commemorating the ships and men of Ivory Soap.

A Memorial Plaque was dedicated there on October 3, 1997. Fred Duncan and other survivors from all three services--Army, Air Corps, Naval Armed Guards, and Merchant Marine assembled in a reunion at Washington, D.C., in October 1998.

Dear reader, if you or anyone you know was part of the historic but invisible operation, please send word to Fred or to me. We merchant marine veterans, at least, can comprehend the risks and perils faced by the Ivory Soap boys, and offer our own sophisticated tribute to these brave shipmates, who helped win the war in the Pacific.

Sources:

The Liberty Ships; The history of the"emergency" type cargo ships constructed in the United States during World War II, L. A. Sawyer and W. H. Mitchell, Cambridge, Maryland: Cornell Maritime Press, 1970

A History of the Army Aircraft Repair Ship Project, Nov. 1943-Sept. 1944, U.S. Army Air Forces, Feb. 14, 1945

Photo of Merchant Marine Officer teaching lifeboat skills to the Army crewmembers courtesy of Fred Duncan