syscom3

Pacific Historian

Only two known and verified American veterans from the Great War remain.

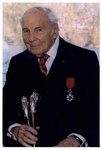

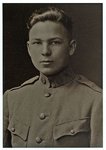

This gentleman is the LAST to have served oversea's in that conflict.

Frank Buckles

Frank Woodruff Buckles (born February 1, 1901) is, at age 106, one of the last two known surviving American-born veterans of the First World War.

The other surviving veteran is Harry Richard Landis. John Babcock is a Canadian-born American who served in the Canadian army during the war.

Buckles is the last living WWI U.S. veteran to finish basic training and be stationed overseas prior to the end of the war. The US Library of Congress included him in its Veterans History Project that has audio, video and pictorial information on Buckles' experiences in both World War I and the Second World War, and which even includes a full 148-minute video interview or the same interview in 11 segments.

He was born in Harrison County, Missouri, and enlisted at the beginning of the United States' involvement in World War I in April 1917. During his time in service for the United States Army, Frank was stationed in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany and France. Buckles was sent to France in 1917 at age 16, where he was a driver; after the Armistice was signed in 1918, he escorted prisoners of war back to Germany. In 1919, after the war had ended, Frank Buckles was stationed in Germany, and he was discharged from service in 1920 having achieved the rank of corporal. In the Second World War, in the 1940s, Buckles was a civilian working for an American shipping line. He was captured by the Japanese, however, and spent three years in a Japanese prison camp during most of that war.

Buckles was awarded the légion d'honneur by then French president Jacques Chirac, and he currently lives in Charles Town, West Virginia. His story was featured on the Memorial Day 2007 episode of NBC Nightly News. He was also at the 2007 Memorial Day parade in Washington, D.C., riding in a buggy.

From an op-ed piece from last month....

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/12/opinion/12rubin.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

Op-Ed Contributor

Over There — and Gone Forever

Article Tools Sponsored By

By RICHARD RUBIN

Published: November 12, 2007

BY any conceivable measure, Frank Buckles has led an extraordinary life. Born on a farm in Missouri in February 1901, he saw his first automobile in his hometown in 1905, and his first airplane at the Illinois State Fair in 1907. At 15 he moved on his own to Oklahoma and went to work in a bank; in the 1940s, he spent more than three years as a Japanese prisoner of war. When he returned to the United States, he married, had a daughter and bought a farm near Charles Town, W. Va., where he lives to this day. He drove a tractor until he was 104.

But even more significant than the remarkable details of Mr. Buckles's life is what he represents: Of the two million soldiers the United States sent to France in World War I, he is the only one left.

This Veterans Day marked the 89th anniversary of the armistice that ended that war. The holiday, first proclaimed as Armistice Day by President Woodrow Wilson in 1919 and renamed in 1954 to honor veterans of all wars, has become, in the minds of many Americans, little more than a point between Halloween and Thanksgiving when banks are closed and mail isn't delivered. But there's a good chance that this Veterans Day will prove to be the last with a living American World War I veteran. (Mr. Buckles is one of only three left; the other two were still in basic training in the United States when the war ended.) Ten died in the last year. The youngest of them was 105.

At the end of his documentary "The War," Ken Burns notes that 1,000 World War II veterans are dying every day. Their passing is being observed at all levels of American society; no doubt you have heard a lot about them in recent days. Fortunately, World War II veterans will be with us for some years yet. There is still time to honor them. But the passing of the last few veterans of the First World War is all but complete, and has gone largely unnoticed here.

Perhaps we shouldn't be surprised. Almost from the moment the armistice took effect, the United States has worked hard, it seems, to forget World War I; maybe that's because more than 100,000 Americans never returned from it, lost for a cause that few can explain even now. The first few who did come home were given ticker-tape parades, but most returned only to silence and a good bit of indifference.

There was no G.I. Bill of Rights to see that they got a college education or vocational training, a mortgage or small-business loan. There was nothing but what remained of the lives they had left behind a year or two earlier, and the hope that they might eventually be able to return to what President Warren Harding, Wilson's successor, would call "normalcy." Prohibition, isolationism, the stock market bubble and the crisis in farming made that hard; the Great Depression, harder still.

A few years ago, I set out to see if I could find any living American World War I veterans. No one — not the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the Veterans of Foreign Wars, or the American Legion — knew how many there were or where they might be. As far as I could tell, no one much seemed to care, either.

Eventually, I did find some, including Frank Buckles, who was 102 when we first met. Eighty-six years earlier, he'd lied about his age to enlist. The Army sent him to England but, itching to be near the action, he managed to get himself sent on to France, though never to the trenches.

After the armistice, he was assigned to guard German prisoners waiting to be repatriated. Seeing that he was still just a boy, the prisoners adopted him, taught him their language, gave him food from their Red Cross packages, bits of their uniforms to take home as souvenirs.

In the 1930s, while working for a steamship company, Mr. Buckles visited Germany; it was difficult for him to reconcile his fond memories of those old P.O.W.'s with what he saw of life under the Third Reich. The steamship company later sent him to run its office in Manila; he was there in January 1942 when the Japanese occupied the city and took him prisoner. At some point during his 39 months in captivity, he contracted beriberi, which affects his sense of balance even now, almost 63 years after he was liberated by the 11th Airborne Division.

Nevertheless, he carries with aplomb the burden of being the last of his kind. "For a long time I've felt that there should be more recognition of the surviving veterans of World War I," he tells me; now that group is, more or less, him. How does he feel about that? "Someone has to do it," he says blithely, but adds: "It kind of startles you."

Four years ago, I attended a Veterans Day observance in Orleans, Mass. Near the head of the parade, a 106-year-old named J. Laurence Moffitt rode in a Japanese sedan, waving to the small crowd of onlookers and sporting the same helmet he had been wearing in the Argonne Forest at the moment the armistice took effect, 85 years earlier.

I didn't know it then, but that was, in all likelihood, the last small-town American Veterans Day parade to feature a World War I veteran. The years since have seen the passing of one last after another — the last combat-wounded veteran, the last Marine, the last African-American, the last Yeomanette — until, now, we are down to the last of the last.

It's hard for anyone, I imagine, to say for certain what it is that we will lose when Frank Buckles dies. It's not that World War I will then become history; it's been history for a long time now. But it will become a different kind of history, the kind we can't quite touch anymore, the kind that will, from that point on, always be just beyond our grasp somehow. We can't stop that from happening. But we should, at least, take notice of it.

This gentleman is the LAST to have served oversea's in that conflict.

Frank Buckles

Frank Woodruff Buckles (born February 1, 1901) is, at age 106, one of the last two known surviving American-born veterans of the First World War.

The other surviving veteran is Harry Richard Landis. John Babcock is a Canadian-born American who served in the Canadian army during the war.

Buckles is the last living WWI U.S. veteran to finish basic training and be stationed overseas prior to the end of the war. The US Library of Congress included him in its Veterans History Project that has audio, video and pictorial information on Buckles' experiences in both World War I and the Second World War, and which even includes a full 148-minute video interview or the same interview in 11 segments.

He was born in Harrison County, Missouri, and enlisted at the beginning of the United States' involvement in World War I in April 1917. During his time in service for the United States Army, Frank was stationed in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany and France. Buckles was sent to France in 1917 at age 16, where he was a driver; after the Armistice was signed in 1918, he escorted prisoners of war back to Germany. In 1919, after the war had ended, Frank Buckles was stationed in Germany, and he was discharged from service in 1920 having achieved the rank of corporal. In the Second World War, in the 1940s, Buckles was a civilian working for an American shipping line. He was captured by the Japanese, however, and spent three years in a Japanese prison camp during most of that war.

Buckles was awarded the légion d'honneur by then French president Jacques Chirac, and he currently lives in Charles Town, West Virginia. His story was featured on the Memorial Day 2007 episode of NBC Nightly News. He was also at the 2007 Memorial Day parade in Washington, D.C., riding in a buggy.

From an op-ed piece from last month....

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/12/opinion/12rubin.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

Op-Ed Contributor

Over There — and Gone Forever

Article Tools Sponsored By

By RICHARD RUBIN

Published: November 12, 2007

BY any conceivable measure, Frank Buckles has led an extraordinary life. Born on a farm in Missouri in February 1901, he saw his first automobile in his hometown in 1905, and his first airplane at the Illinois State Fair in 1907. At 15 he moved on his own to Oklahoma and went to work in a bank; in the 1940s, he spent more than three years as a Japanese prisoner of war. When he returned to the United States, he married, had a daughter and bought a farm near Charles Town, W. Va., where he lives to this day. He drove a tractor until he was 104.

But even more significant than the remarkable details of Mr. Buckles's life is what he represents: Of the two million soldiers the United States sent to France in World War I, he is the only one left.

This Veterans Day marked the 89th anniversary of the armistice that ended that war. The holiday, first proclaimed as Armistice Day by President Woodrow Wilson in 1919 and renamed in 1954 to honor veterans of all wars, has become, in the minds of many Americans, little more than a point between Halloween and Thanksgiving when banks are closed and mail isn't delivered. But there's a good chance that this Veterans Day will prove to be the last with a living American World War I veteran. (Mr. Buckles is one of only three left; the other two were still in basic training in the United States when the war ended.) Ten died in the last year. The youngest of them was 105.

At the end of his documentary "The War," Ken Burns notes that 1,000 World War II veterans are dying every day. Their passing is being observed at all levels of American society; no doubt you have heard a lot about them in recent days. Fortunately, World War II veterans will be with us for some years yet. There is still time to honor them. But the passing of the last few veterans of the First World War is all but complete, and has gone largely unnoticed here.

Perhaps we shouldn't be surprised. Almost from the moment the armistice took effect, the United States has worked hard, it seems, to forget World War I; maybe that's because more than 100,000 Americans never returned from it, lost for a cause that few can explain even now. The first few who did come home were given ticker-tape parades, but most returned only to silence and a good bit of indifference.

There was no G.I. Bill of Rights to see that they got a college education or vocational training, a mortgage or small-business loan. There was nothing but what remained of the lives they had left behind a year or two earlier, and the hope that they might eventually be able to return to what President Warren Harding, Wilson's successor, would call "normalcy." Prohibition, isolationism, the stock market bubble and the crisis in farming made that hard; the Great Depression, harder still.

A few years ago, I set out to see if I could find any living American World War I veterans. No one — not the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the Veterans of Foreign Wars, or the American Legion — knew how many there were or where they might be. As far as I could tell, no one much seemed to care, either.

Eventually, I did find some, including Frank Buckles, who was 102 when we first met. Eighty-six years earlier, he'd lied about his age to enlist. The Army sent him to England but, itching to be near the action, he managed to get himself sent on to France, though never to the trenches.

After the armistice, he was assigned to guard German prisoners waiting to be repatriated. Seeing that he was still just a boy, the prisoners adopted him, taught him their language, gave him food from their Red Cross packages, bits of their uniforms to take home as souvenirs.

In the 1930s, while working for a steamship company, Mr. Buckles visited Germany; it was difficult for him to reconcile his fond memories of those old P.O.W.'s with what he saw of life under the Third Reich. The steamship company later sent him to run its office in Manila; he was there in January 1942 when the Japanese occupied the city and took him prisoner. At some point during his 39 months in captivity, he contracted beriberi, which affects his sense of balance even now, almost 63 years after he was liberated by the 11th Airborne Division.

Nevertheless, he carries with aplomb the burden of being the last of his kind. "For a long time I've felt that there should be more recognition of the surviving veterans of World War I," he tells me; now that group is, more or less, him. How does he feel about that? "Someone has to do it," he says blithely, but adds: "It kind of startles you."

Four years ago, I attended a Veterans Day observance in Orleans, Mass. Near the head of the parade, a 106-year-old named J. Laurence Moffitt rode in a Japanese sedan, waving to the small crowd of onlookers and sporting the same helmet he had been wearing in the Argonne Forest at the moment the armistice took effect, 85 years earlier.

I didn't know it then, but that was, in all likelihood, the last small-town American Veterans Day parade to feature a World War I veteran. The years since have seen the passing of one last after another — the last combat-wounded veteran, the last Marine, the last African-American, the last Yeomanette — until, now, we are down to the last of the last.

It's hard for anyone, I imagine, to say for certain what it is that we will lose when Frank Buckles dies. It's not that World War I will then become history; it's been history for a long time now. But it will become a different kind of history, the kind we can't quite touch anymore, the kind that will, from that point on, always be just beyond our grasp somehow. We can't stop that from happening. But we should, at least, take notice of it.

to them all and for every veteran.

to them all and for every veteran.