seesul

Senior Master Sergeant

Hello,

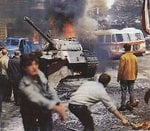

today we have a sad 40th anniversary of the Soviet occupation of our country...

source: Prague Spring - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Prague Spring (Czech: Pražské jaro, Slovak: Pražská jar)

was a period of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia during the era of its domination by the Soviet Union after World War II. It began on January 5, 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček came to power, and continued until August 21, when the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies invaded the country to halt the reforms.

The Prague Spring reforms were an attempt by Dubček to grant additional rights to the citizens in an act of partial decentralization of the economy and democratization. Among the freedoms granted were a loosening of restrictions on the media, speech and travel. Dubček also federalized the country into two separate republics; this was the only change that survived the end of the Prague Spring.

The reforms were not received well by the Soviets who, after failed negotiations, sent thousands of Warsaw Pact troops and tanks to occupy the country. A large wave of emigration swept the nation. While there were many non-violent protests in the country, including the protest-suicide of a student, there was no military resistance. Czechoslovakia remained occupied until 1990.

After the invasion, Czechoslovakia entered a period of normalization: subsequent leaders attempted to restore the political and economic values that had prevailed before Dubček gained control of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ). Gustáv Husák, who replaced Dubček and also became president, reversed almost all of Dubček's reforms. The Prague Spring has become immortalized in music and literature such as the work of Karel Kryl and Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

Background

The process of destalinization in Czechoslovakia had begun under Antonín Novotný in the early 1960s, but had progressed slower than in most other socialist states of the Eastern Bloc.[1] Following the lead of Nikita Khrushchev, Novotný proclaimed the completion of socialism, and the new constitution,[2] accordingly, adopted the name Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. The pace of change, however, was sluggish; the rehabilitation of Stalinist-era victims, such as those convicted in the Slánský trials, may have been considered as early as 1963, but did not take place until 1967.[3] As the strict regime eased its rules, the Union of Czechoslovak Writers cautiously began to air discontent, and in the union's gazette, Literární noviny, members suggested that literature should be independent of Party doctrine.[4]

In June 1967, a small fraction of the Czech writer's union sympathized with radical socialists, specifically Ludvík Vaculík, Milan Kundera, Jan Procházka, Antonín Jaroslav Liehm, Pavel Kohout and Ivan Klíma.[4] A few months later, at a party meeting, it was decided that administrative actions against the writers who openly expressed support of reformation would be taken. Since only a small part of the union held these beliefs, the remaining members were relied upon to discipline their colleagues.[4] Control over Literární noviny and several other publishing houses was transferred to the ministry of culture,[4] and even members of the party who later became major reformers—including Dubček—endorsed these moves.[4]

In the early 1960s, Czechoslovakia, then officially known as the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR), underwent an economic downturn.[5] The Soviet model of industrialization applied poorly to Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia was already quite industrialized before World War II and the Soviet model mainly took into account less developed economies. Novotný's attempt at restructuring the economy, the 1965 New Economic Model, spurred increased demand for political reform as well.[6]

By 1967, president Antonín Novotný was losing support. First Secretary of the regional Communist Party of Slovakia, Alexander Dubček, and economist Ota Šik challenged him at a meeting of the Central Committee, and Dubček invited Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev to Prague that December.[7] Brezhnev was surprised at the extent of the opposition to Novotný and supported his removal as Czechoslovakia's leader. Dubček thus replaced Novotný as First Secretary on January 5, 1968.[8] On March 22, 1968, Novotný resigned his presidency and was replaced by Ludvík Svoboda, who later gave consent to the reforms.[9]

Liberalization and reform

The Czechoslovak public knew nothing of the political infighting, and early signs of change were few. When the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) Presidium member Josef Smrkovský was interviewed in a Rudé Právo article, entitled "What Lies Ahead", he insisted that Dubček's appointment at the January Plenum would further the goals of socialism and maintain the working-class nature of the Communist Party.[10]

On the 20th anniversary of Czechoslovakia's "Victorious February", Dubček delivered a speech explaining the need for change following the triumph of socialism. He emphasized the need to "enforce the leading role of the party more effectively"[11] and acknowledged that, despite Klement Gottwald's urgings for better relations with society, the Party had too often made heavy-handed rulings on trivial issues. Dubček declared the party's mission was "to build an advanced socialist society on sound economic foundations ... a socialism that corresponds to the historical democratic traditions of Czechoslovakia, in accordance with the experience of other communist parties ..."[11]

In April, Dubček launched an "Action Program" of liberalizations, which included increasing freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and freedom of movement, with economic emphasis on consumer goods and the possibility of a multiparty government. The program was based on the view that "Socialism cannot mean only liberation of the working people from the domination of exploiting class relations, but must make more provisions for a fuller life of the personality than any bourgeois democracy."[12] The program would limit the power of the secret police[13] and provide for the federalization of the ČSSR into two equal nations.[14] The Program also covered foreign policy, including both the maintenance of good relations with Western countries and cooperation with the Soviet Union and other communist nations.[15] It spoke of a ten year transition through which democratic elections would be made possible and a new form of democratic socialism would replace the status quo.[16]

Those who drafted the Program, however, were careful not to criticize the actions of the post-war communist regime, only to point out policies that they felt had outlived their usefulness.[17] For instance, the immediate post-war situation had required "centralist and directive-administrative methods"[17] to fight against the "remnants of the bourgeoisie."[17] Since the "antagonistic classes"[17] were said to have been defeated with the achievement of socialism, these methods were no longer necessary. Reform was needed, stated the Program, for the Czechoslovak economy to join the "scientific-technical revolution in the world"[17] rather than relying on Stalinist-era heavy industry, labor power, and raw materials.[17] Furthermore, since internal class conflict had been overcome, workers could now be duly rewarded for their qualifications and technical skills without contravening Marxist-Leninism. The Program suggested it was now necessary to ensure important positions were "filled by capable, educated socialist expert cadres" in order to compete with capitalism.[17]

Although the Action Program stipulated that reform must proceed under KSČ direction, popular pressure mounted to implement reforms immediately.[18] Radical elements became more vocal: anti-Soviet polemics appeared in the press (after the formal abolishment of censorship on June 26, 1968 ),[16] the Social Democrats began to form a separate party, and new unaffiliated political clubs were created. Party conservatives urged repressive measures, but Dubček counseled moderation and reemphasized KSČ leadership.[19] At the Presidium of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in April, Dubček announced a political program of "socialism with a human face".[20] In May, he announced that the Fourteenth Party Congress would convene in an early session on September 9. The congress would incorporate the Action Program into the party statutes, draft a federalization law, and elect a new Central Committee.[21]

Dubček's reforms guaranteed freedom of the press, and political commentary was allowed for the first time in mainstream media.[22] At the time of the Prague Spring, Czechoslovak exports were declining in competitiveness, and Dubček's reforms planned to solve these troubles by mixing planned and market economies. Within the party, there were varying opinions on how this should proceed; certain economists wished for a more mixed economy while others wanted the economy to remain mostly socialist. Dubček continued to stress the importance of economic reform proceeding under Communist Party rule.[23]

On June 27, Ludvík Vaculík, a leading author and journalist, published a manifesto titled The Two Thousand Words. It expressed concern about conservative elements within the KSČ and so-called "foreign" forces. Vaculík called on the people to take the initiative in implementing the reform program.[24] Dubček, the party Presidium, the National Front, and the cabinet denounced this manifesto.

today we have a sad 40th anniversary of the Soviet occupation of our country...

source: Prague Spring - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Prague Spring (Czech: Pražské jaro, Slovak: Pražská jar)

was a period of political liberalization in Czechoslovakia during the era of its domination by the Soviet Union after World War II. It began on January 5, 1968, when reformist Alexander Dubček came to power, and continued until August 21, when the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies invaded the country to halt the reforms.

The Prague Spring reforms were an attempt by Dubček to grant additional rights to the citizens in an act of partial decentralization of the economy and democratization. Among the freedoms granted were a loosening of restrictions on the media, speech and travel. Dubček also federalized the country into two separate republics; this was the only change that survived the end of the Prague Spring.

The reforms were not received well by the Soviets who, after failed negotiations, sent thousands of Warsaw Pact troops and tanks to occupy the country. A large wave of emigration swept the nation. While there were many non-violent protests in the country, including the protest-suicide of a student, there was no military resistance. Czechoslovakia remained occupied until 1990.

After the invasion, Czechoslovakia entered a period of normalization: subsequent leaders attempted to restore the political and economic values that had prevailed before Dubček gained control of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ). Gustáv Husák, who replaced Dubček and also became president, reversed almost all of Dubček's reforms. The Prague Spring has become immortalized in music and literature such as the work of Karel Kryl and Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

Background

The process of destalinization in Czechoslovakia had begun under Antonín Novotný in the early 1960s, but had progressed slower than in most other socialist states of the Eastern Bloc.[1] Following the lead of Nikita Khrushchev, Novotný proclaimed the completion of socialism, and the new constitution,[2] accordingly, adopted the name Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. The pace of change, however, was sluggish; the rehabilitation of Stalinist-era victims, such as those convicted in the Slánský trials, may have been considered as early as 1963, but did not take place until 1967.[3] As the strict regime eased its rules, the Union of Czechoslovak Writers cautiously began to air discontent, and in the union's gazette, Literární noviny, members suggested that literature should be independent of Party doctrine.[4]

In June 1967, a small fraction of the Czech writer's union sympathized with radical socialists, specifically Ludvík Vaculík, Milan Kundera, Jan Procházka, Antonín Jaroslav Liehm, Pavel Kohout and Ivan Klíma.[4] A few months later, at a party meeting, it was decided that administrative actions against the writers who openly expressed support of reformation would be taken. Since only a small part of the union held these beliefs, the remaining members were relied upon to discipline their colleagues.[4] Control over Literární noviny and several other publishing houses was transferred to the ministry of culture,[4] and even members of the party who later became major reformers—including Dubček—endorsed these moves.[4]

In the early 1960s, Czechoslovakia, then officially known as the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR), underwent an economic downturn.[5] The Soviet model of industrialization applied poorly to Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia was already quite industrialized before World War II and the Soviet model mainly took into account less developed economies. Novotný's attempt at restructuring the economy, the 1965 New Economic Model, spurred increased demand for political reform as well.[6]

By 1967, president Antonín Novotný was losing support. First Secretary of the regional Communist Party of Slovakia, Alexander Dubček, and economist Ota Šik challenged him at a meeting of the Central Committee, and Dubček invited Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev to Prague that December.[7] Brezhnev was surprised at the extent of the opposition to Novotný and supported his removal as Czechoslovakia's leader. Dubček thus replaced Novotný as First Secretary on January 5, 1968.[8] On March 22, 1968, Novotný resigned his presidency and was replaced by Ludvík Svoboda, who later gave consent to the reforms.[9]

Liberalization and reform

The Czechoslovak public knew nothing of the political infighting, and early signs of change were few. When the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) Presidium member Josef Smrkovský was interviewed in a Rudé Právo article, entitled "What Lies Ahead", he insisted that Dubček's appointment at the January Plenum would further the goals of socialism and maintain the working-class nature of the Communist Party.[10]

On the 20th anniversary of Czechoslovakia's "Victorious February", Dubček delivered a speech explaining the need for change following the triumph of socialism. He emphasized the need to "enforce the leading role of the party more effectively"[11] and acknowledged that, despite Klement Gottwald's urgings for better relations with society, the Party had too often made heavy-handed rulings on trivial issues. Dubček declared the party's mission was "to build an advanced socialist society on sound economic foundations ... a socialism that corresponds to the historical democratic traditions of Czechoslovakia, in accordance with the experience of other communist parties ..."[11]

In April, Dubček launched an "Action Program" of liberalizations, which included increasing freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and freedom of movement, with economic emphasis on consumer goods and the possibility of a multiparty government. The program was based on the view that "Socialism cannot mean only liberation of the working people from the domination of exploiting class relations, but must make more provisions for a fuller life of the personality than any bourgeois democracy."[12] The program would limit the power of the secret police[13] and provide for the federalization of the ČSSR into two equal nations.[14] The Program also covered foreign policy, including both the maintenance of good relations with Western countries and cooperation with the Soviet Union and other communist nations.[15] It spoke of a ten year transition through which democratic elections would be made possible and a new form of democratic socialism would replace the status quo.[16]

Those who drafted the Program, however, were careful not to criticize the actions of the post-war communist regime, only to point out policies that they felt had outlived their usefulness.[17] For instance, the immediate post-war situation had required "centralist and directive-administrative methods"[17] to fight against the "remnants of the bourgeoisie."[17] Since the "antagonistic classes"[17] were said to have been defeated with the achievement of socialism, these methods were no longer necessary. Reform was needed, stated the Program, for the Czechoslovak economy to join the "scientific-technical revolution in the world"[17] rather than relying on Stalinist-era heavy industry, labor power, and raw materials.[17] Furthermore, since internal class conflict had been overcome, workers could now be duly rewarded for their qualifications and technical skills without contravening Marxist-Leninism. The Program suggested it was now necessary to ensure important positions were "filled by capable, educated socialist expert cadres" in order to compete with capitalism.[17]

Although the Action Program stipulated that reform must proceed under KSČ direction, popular pressure mounted to implement reforms immediately.[18] Radical elements became more vocal: anti-Soviet polemics appeared in the press (after the formal abolishment of censorship on June 26, 1968 ),[16] the Social Democrats began to form a separate party, and new unaffiliated political clubs were created. Party conservatives urged repressive measures, but Dubček counseled moderation and reemphasized KSČ leadership.[19] At the Presidium of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in April, Dubček announced a political program of "socialism with a human face".[20] In May, he announced that the Fourteenth Party Congress would convene in an early session on September 9. The congress would incorporate the Action Program into the party statutes, draft a federalization law, and elect a new Central Committee.[21]

Dubček's reforms guaranteed freedom of the press, and political commentary was allowed for the first time in mainstream media.[22] At the time of the Prague Spring, Czechoslovak exports were declining in competitiveness, and Dubček's reforms planned to solve these troubles by mixing planned and market economies. Within the party, there were varying opinions on how this should proceed; certain economists wished for a more mixed economy while others wanted the economy to remain mostly socialist. Dubček continued to stress the importance of economic reform proceeding under Communist Party rule.[23]

On June 27, Ludvík Vaculík, a leading author and journalist, published a manifesto titled The Two Thousand Words. It expressed concern about conservative elements within the KSČ and so-called "foreign" forces. Vaculík called on the people to take the initiative in implementing the reform program.[24] Dubček, the party Presidium, the National Front, and the cabinet denounced this manifesto.