- Thread starter

- #21

In 1935 the Air Ministry had issued two specifications, M.15/35 and G.24/35, which detailed requirements for a torpedo-bomber and a general reconnaissance/ bomber respectively. The latter was required to replace the Avro Anson in service for this role and. as mentioned in the Bristol Blenheim entry, was to be met by the Bristol Type 149 which was built in Canada as the Bolingbroke. To meet the first requirement, for a torpedo-bomber, Bristol began by considering an adaptation of the Blenheim, identifying its design as the Type 150. This proposal, which was concerned primarily with a change in fuselage design to provide accommodation for a torpedo and the installation of more powerful engines, was submitted to the Air Ministry in November 1935.

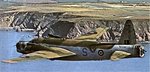

After sending off these details of the Type 150, the Bristol design team came to the conclusion that it would be possible to meet both of the Air Ministry's specifications by a single aircraft evolved from the Blenheim, and immediately prepared a new design outline, the Type 152. By comparison with the Blenheim Mk IV, the new design was increased slightly in length to allow for the carriage of a torpedo in a semi-exposed position, provided a navigation station, and seated pilot and navigator side-by-side. Behind them were radio and camera positions which would be manned by a gunner/camera/radio operator. The Type 152 was more attractive to the Air Ministry, but it was considered that a crew of four was essential, and the accommodation was redesigned to this end. The resulting high roofline, which continued unbroken to the dorsal turret, became a distinguishing feature of this new aircraft, built to Air Ministry Specification 10/36, and subsequently named Beaufort.

Detail design was initiated immediately, but early analysis and estimates showed that the intended powerplant of two Bristol Perseus engines would provide insufficient power to cater for the increase of almost 25 per cent in gross weight without a serious loss of performance. Instead, the newly developed twin-row Taurus sleeve-valve engine was selected for the Beaufort, the only concern being whether it would be cleared for production in time to coincide with the construction of the new airframe. The initial contract, for 78 aircraft, was placed in August 1936, but the first prototype did not fly until just over two years later, on 15 October 1938. There had been a number of reasons for this long period of labour, one being overheating problems with the powerplant, and another the need to disperse the Blenheim production line to shadow factories before the Beaufort could be built.

After sending off these details of the Type 150, the Bristol design team came to the conclusion that it would be possible to meet both of the Air Ministry's specifications by a single aircraft evolved from the Blenheim, and immediately prepared a new design outline, the Type 152. By comparison with the Blenheim Mk IV, the new design was increased slightly in length to allow for the carriage of a torpedo in a semi-exposed position, provided a navigation station, and seated pilot and navigator side-by-side. Behind them were radio and camera positions which would be manned by a gunner/camera/radio operator. The Type 152 was more attractive to the Air Ministry, but it was considered that a crew of four was essential, and the accommodation was redesigned to this end. The resulting high roofline, which continued unbroken to the dorsal turret, became a distinguishing feature of this new aircraft, built to Air Ministry Specification 10/36, and subsequently named Beaufort.

Detail design was initiated immediately, but early analysis and estimates showed that the intended powerplant of two Bristol Perseus engines would provide insufficient power to cater for the increase of almost 25 per cent in gross weight without a serious loss of performance. Instead, the newly developed twin-row Taurus sleeve-valve engine was selected for the Beaufort, the only concern being whether it would be cleared for production in time to coincide with the construction of the new airframe. The initial contract, for 78 aircraft, was placed in August 1936, but the first prototype did not fly until just over two years later, on 15 October 1938. There had been a number of reasons for this long period of labour, one being overheating problems with the powerplant, and another the need to disperse the Blenheim production line to shadow factories before the Beaufort could be built.