- Thread starter

- #21

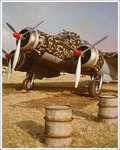

The Savoia-Marchetti SM.82 Marsupiale (en: Marsupial) was an Italian bomber and transport aircraft of World War II. It was a cantilever, mid-wing monoplane trimotor with a retractable, tailwheel undercarriage. About 400 were built, the first entering service in 1940, but although able to operate as a bomber with a maximum bombload of up to 8,818 lb (4000 kg), the SM.82 saw very limited use in this role. The SM.82 Marsupiale was developed from the earlier SM.75 Marsupiale civil transport as a heavy bomber and military transport. Although having the same configuration of the SM.75, the SM.82 was larger. The aircraft was quickly developed and the prototype first flew in 1939. Although underpowered and slow, it was capable of carrying heavy loads, including the L3 light tank and a complete disassembled CR.42 fighter (these loads demanded special modifications, though). It had both cargo and troop transport capability, with room up to 40 men and their equipment. Deliveries to the Regia Aeronautica began in 1940. However, production rates were slow, with only 100 aircraft delivered in 1940, and another 100 in 1941, so that there were never enough of these aircraft in service. By 1942 production doubled to 200 a year, while in 1944 almost 300 were produced, by which time the factory was under the control of the Germans.

Attachments

Last edited: