Unlike the Germans… lmao

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

the invention of the turbojet. A letter that changed history

- Thread starter Dronescapes

- Start date

Ad: This forum contains affiliate links to products on Amazon and eBay. More information in Terms and rules

More options

Who Replied?Shortround6

Lieutenant General

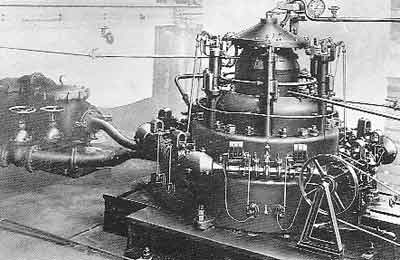

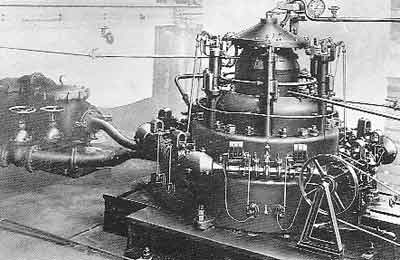

people had been working on gas turbines for years. See for one example.

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

There are several paragraphs on gas turbines in the engineering section of "The Naval Annual 1913" edited by Viscount Hythe for example. They knew about the theory and were wondering where it would lead even if it wasn't practical yet.

However there were several problems, one was that industrial or marine turbines were at least an order of magnitude heavier than aircraft engines for the power produced and the 2nd was that the compressors were horribly inefficient. Early experimental engines barely ran, the compressors needing all the power the turbine could generate, leaving little or no power for the output shaft. This did influence later evaluations negatively.

Like I said, the concept was simple. Simply stack axial compressor stages to get the compression ratio you want, stick in a (or more than one) combustion chamber and send the exhaust threw the turbine section to power the compressor, power a shaft and exit the engine producing thrust.

Trouble was that you could not just stack the compressor sections. Each section needed different pitch blades and stators and often different diameters (volume in the stage) to actually work. At times one (or more stages) actually decreased the compression of the stage/s ahead of it.

Even in the early 1920s there was much discussion on compressors and the US actually built a test flew a plane using a Roots supercharger to compare to centrifugal supercharger. The Roots supercharger was better than no supercharger but that was about it. Most aircraft superchargers of the 1920s and early 30s were not offering even 2 to 1 compression ratios.

So that was step #1. Get a compressor section that will allow the engine to start, run and stay running. You can't even work on the combustion chambers if the compressor won't supply air (well you can using a large industrial compressor but then?). Granted a turbojet doesn't have a turbine sucking power out of the exhaust stream like a turboshaft/turboprop does.

For some reason there were engine designers/companies that tried to build turboprops before they had working turbojets. Yeah, let's design a more complicated turbine section and high power reduction gear before we even get the basic engine to run

Whittle did keep it as simple as possible although the burner/combustion chamber was bit much. But again, you needed a working burner/combustion chamber to study before you could make modifications.

More money could help but more money sometimes isn't going to speed up development of alloys or some other parts much. And even if you can get something to work in a tool room example, can you mass produce it?

Holzwarth gas turbine - Wikipedia

There are several paragraphs on gas turbines in the engineering section of "The Naval Annual 1913" edited by Viscount Hythe for example. They knew about the theory and were wondering where it would lead even if it wasn't practical yet.

However there were several problems, one was that industrial or marine turbines were at least an order of magnitude heavier than aircraft engines for the power produced and the 2nd was that the compressors were horribly inefficient. Early experimental engines barely ran, the compressors needing all the power the turbine could generate, leaving little or no power for the output shaft. This did influence later evaluations negatively.

Like I said, the concept was simple. Simply stack axial compressor stages to get the compression ratio you want, stick in a (or more than one) combustion chamber and send the exhaust threw the turbine section to power the compressor, power a shaft and exit the engine producing thrust.

Trouble was that you could not just stack the compressor sections. Each section needed different pitch blades and stators and often different diameters (volume in the stage) to actually work. At times one (or more stages) actually decreased the compression of the stage/s ahead of it.

Even in the early 1920s there was much discussion on compressors and the US actually built a test flew a plane using a Roots supercharger to compare to centrifugal supercharger. The Roots supercharger was better than no supercharger but that was about it. Most aircraft superchargers of the 1920s and early 30s were not offering even 2 to 1 compression ratios.

So that was step #1. Get a compressor section that will allow the engine to start, run and stay running. You can't even work on the combustion chambers if the compressor won't supply air (well you can using a large industrial compressor but then?). Granted a turbojet doesn't have a turbine sucking power out of the exhaust stream like a turboshaft/turboprop does.

For some reason there were engine designers/companies that tried to build turboprops before they had working turbojets. Yeah, let's design a more complicated turbine section and high power reduction gear before we even get the basic engine to run

Whittle did keep it as simple as possible although the burner/combustion chamber was bit much. But again, you needed a working burner/combustion chamber to study before you could make modifications.

More money could help but more money sometimes isn't going to speed up development of alloys or some other parts much. And even if you can get something to work in a tool room example, can you mass produce it?

- Thread starter

- #23

Dronescapes

Senior Airman

Yet the first operational jet, the F-80 Shooting Star was equipped with Whittle's turbojet...The Americans had decided, as early as 1943, to invest in the Halford (rather than the Whittle) engine. Vide RG 107, NACP.

View attachment 754640

It ended up fighting MiG15s in Korea in the 50s, which were oddly equipped with the same engine but were vastly superior to the U.S. plane, leading the U.S. to send their first axial turbojet aircraft to the conflict, like the F-86

Shortround6

Lieutenant General

This is kind of an over simplification. Both engines were several generations removed from the original Whittle engines and aside from a centrifugal compressor in front, burner cans in the middle and a turbine out the back (Whittle engines folded the burner cans around and the turbine was much closer to the compressor) didn't share much.Yet the first operational jet, the F-80 Shooting Star was equipped with Whittle's turbojet...

It ended up fighting MiG15s in Korea in the 50s, which were oddly equipped with the same engine but were vastly superior to the U.S. plane, leading the U.S. to send their first axial turbojet aircraft to the conflict, like the F-86

GE followed their own development path through a series of "I" engines and RR followed their own path through the Derwent and then the Nene.

I would note that some of the early axial turbojet fighters were not the answer for air to air combat either. Like the F-84 with the Allison J-35 engines.

- Thread starter

- #25

Dronescapes

Senior Airman

You are right, it is oversimplified, but, especially in the early stages, things evolve quite rapidly, especially when rather than being an almost pennyless inventor, you have the resources to do so. Perhaps that is why G.E. is so grateful to him to this day, which is quite surprising, considering he was not American, and more than 80 years went by since he was shipped to the U.S. together with his engine.This is kind of an over simplification. Both engines were several generations removed from the original Whittle engines and aside from a centrifugal compressor in front, burner cans in the middle and a turbine out the back (Whittle engines folded the burner cans around and the turbine was much closer to the compressor) didn't share much.

GE followed their own development path through a series of "I" engines and RR followed their own path through the Derwent and then the Nene.

I would note that some of the early axial turbojet fighters were not the answer for air to air combat either. Like the F-84 with the Allison J-35 engines.

The MiG's story is also quite an interesting twist.

We have contributed to porting to digital a series of 16mm films with Whittle's interviews (we had them scanned at Pinewood Studios a few months ago), and they are quite interesting to listen to, as only a part of them made it into the original documentary.

We plan to release them soon.

He had to go through a lot, before, and after 1937.

Given how he was treated in his own country, I can only admire his resilience and achievements.

Do you know anything about his work on early afterburner concepts?

Shortround6

Lieutenant General

I don't.Do you know anything about his work on early afterburner concepts?

I do know that he was shown around several other US manufactures/company's that were working on jet engines to try to assist them.

This shows that both you need someone of Whittle's ability and a suitable backup team. Rover was not it.

In the US, Allis-Chambers, Lockheed, Northrop and the NACA all flubbed badly. Whittle looked at Northrop's design and when asked by Jack Northrop his honest opinion he told him he thought the company was wasting it's time. They did not have the staff/facilities to develop the design they were working on (including a eighteen stage compressor).

Westinghouse, despite all their steam turbine experience made running engines, at least at first. Somebody had the bright idea than since jet engines were "so simple" you could take one design and just scale it up or down as needed to get the power you want and the configuration you wanted ( One sketch for the McDonald Phantom showed three 9in jet engines in each wing root). in the late 40s the Navy bet heavy on Westinghouse and was forced to scramble for engines when the later Westinghouse engines crashed and burned (sometimes literally) and were canceled and Westinghouse left the jet engine business.

P&W and Wright were kept out of the Jet engine business by the government to concentrate on piston engines and this may have been a mistake. Both companies had to scramble after WW II ended and P & W hooked up with RR and Wright hooked up with Bristol.

RR was correct when they said they would take the Whittle engine and simplify the hell out it.

It was all the little stuff that had to be worked out, materials has already been mentioned. Lubrication and bearings and vibration where also huge. the W2 Whittle engine ran at 16,750rpm. The little (9.5in Westinghouse) ran at 36,000rpm. Throw a blade or have one crack/break throwing the thing out balance things got beyond interesting in hurry.

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)