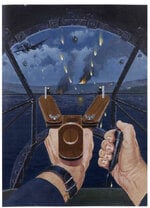

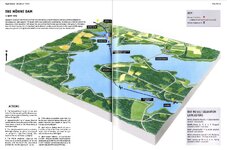

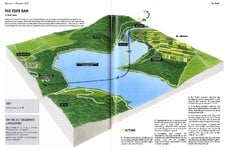

80 years ago today starting at 21:28 19 Avro Lancaster bombers of 617 Squadron RAF took off to attack dams in the Ruhr region of Germany with a unique weapon.

The Mohne and the Eder dams were breached and the Squadron has ever since been known as "The Dambusters"

The RAF lost 53 aircrew killed and 3 captured, with 8 aircraft destroyed.

Two hydroelectric power stations were destroyed and several more damaged. Factories and mines were also damaged and destroyed. An estimated 1,600 civilians – about 600 Germans and 1,000 , mainly Soviet slave labour – were killed by the flooding.

Après moi le déluge

The Mohne and the Eder dams were breached and the Squadron has ever since been known as "The Dambusters"

The RAF lost 53 aircrew killed and 3 captured, with 8 aircraft destroyed.

Two hydroelectric power stations were destroyed and several more damaged. Factories and mines were also damaged and destroyed. An estimated 1,600 civilians – about 600 Germans and 1,000 , mainly Soviet slave labour – were killed by the flooding.

Après moi le déluge